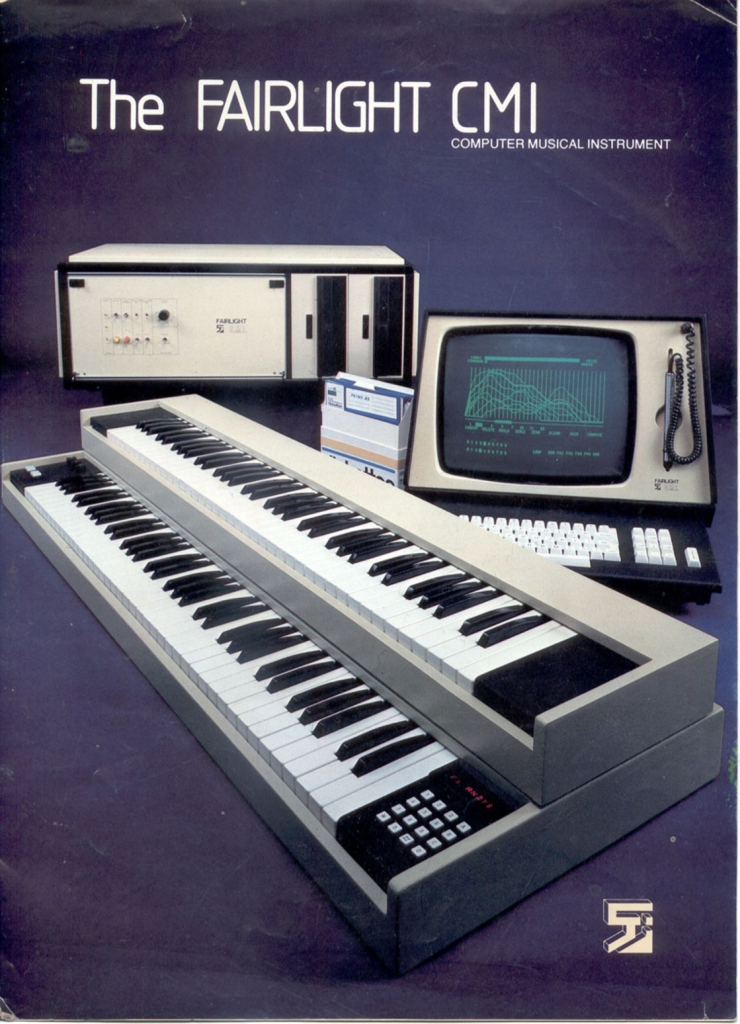

Not An Audiophile – The Podcast featuring podcast episodes with Kim Ryrie, co-founder of the Fairlight Synthesizer and designer of the DEQX processor. In Episode 019 and Part One of the Kim Ryrie story, Kim shares his personal history which is also the history of the Fairlight CMI. In Episode 023 and Part Two, Kim gets excited about his new project DEQX and the potential of this new technology to change home audio forever.

Podcast transcripts below – Episode 019 and Episode 023

TRANSCRIPT

S2 EP023 – 1 simple step to speaker and room sound correction with DEQX and designer, Kim Ryrie.

Glenn Dickens virtually co invented Atmos at Dolby

Kim Ryrie: We’ve got Glenn Dickens. Now Glenn was running R and D at Dolby for 15 years.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: he virtually co invented Atmos at Dolby. He’s now working for us as we speak. He’s in the room next door on the blower with Joe, trying to sort out a time alignment issue in, in the, the Bass integration algorithm.

Episode 23, season two of Audiophile features Kim Ryrie on DEQX

Andrew Hutchison: And welcome back to not an Audiophile.

Andrew Hutchison: This is episode 23, season two. Today we speak to Kim Ryrie in part two.

Andrew Hutchison: I said it would be a week, it’s been weeks. I apologize for that. But we’re now back.

Andrew Hutchison: Brad and myself, speak to Kim , make little titters and comments and probably talk over each other a bit too much. We were highly enthusiastic.

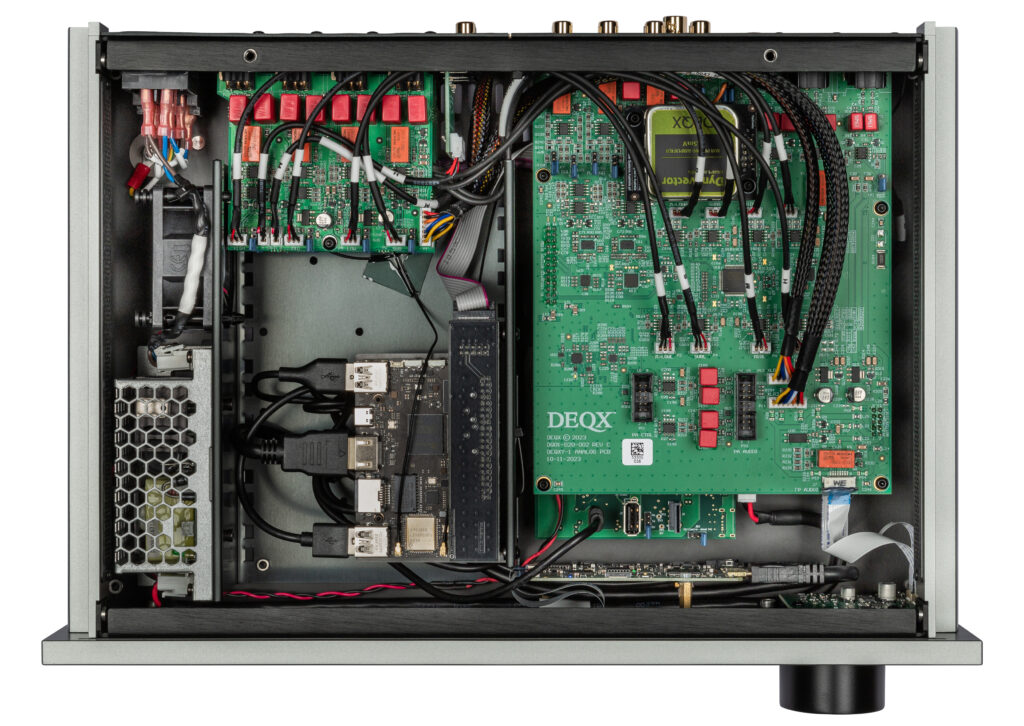

Andrew Hutchison: We just seen downstairs where the

Andrew Hutchison: DEQX product was manufactured.

Andrew Hutchison: We met a number of the

Andrew Hutchison: Incredible people that are involved and frankly we were a little awestruck. Kim today in part two tells us.

Andrew Hutchison: Really how DEQX got a start, what.

Andrew Hutchison: It really is, what it does, and how Gen4 is a significant improvement in refinement over the previous generations.

Meet Spectraflora, Australia’s newest loudspeaker innovator

This episode of not an Audiophile. The podcast is sponsored by Spectraflora. Looking for gorgeous speakers that sound as good as they look. Meet Spectraflora, Australia’s newest loudspeaker innovator. Their flagship Celata 88 is handcrafted in Victoria, Australia. With patent pending waveguide and subwoofer designs, this speaker delivers impactful, dynamic and emotionally gripping sound. Listeners rave about the beauty and breathtaking.

Andrew Hutchison: Sound of the Celata 88 at makes ordinary speakers feel lifeless.

Andrew Hutchison: Experience Spectraflora rediscover meaning in music. Learn more@spectraflora.com great to have you back.

Andrew Hutchison: In the room, Kim. it’s been matter of minutes since we finished episode one and now we’re recording episode two. But we’re going to strike while I, Brad Serhan’s here as well to help us. the deck story started a lot longer ago than people realize and as you’ve joked, the the oldest startup in the history of startups. I mean 96, I think you just.

Kim Ryrie: 97.

Andrew Hutchison: 97, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Look, the triggered I should say.

Andrew Hutchison: By your, from the previous episode, your amazement, perhaps at how well analog active loudspeakers worked.

Kim Ryrie: That’s right.

Andrew Hutchison: And so no doubt there’s a connection between that experience with the Arty Jack band.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So, so just.

Andrew Hutchison: And why you started DEQX. Yes.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So just to recap on that story, we had a band back in the would have been early 70s and and we had a pair of Altec A7 voice of the theatre speakers using the passive crossovers that come with those. And we were blowing the horns up almost every month or two we’d blow the diaphragms up on the horn. and at the time I had a couple of hundred watt amp modules and someone suggested taking them active, which meant having one amp for the horn and another amp for the 15 inch woofer. And then I just built a four pole, 20, four decibels, per octave crossover in front of each amp. And what amazed us was just how clean suddenly the voice of the theatres became. And because of the steeper crossovers we stopped blowing up the horn.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: So that was my first realization of the advantages of active, especially for clarity, you know, minute, you know, reducing crossover distortion in particular. because you know the, for example with a passive crossover you’ve got a 15 inch woofer, that woofer, ah, if it’s got a slow roll off above the crossover frequency. I think the crossover to the horn was about 700 hertz or something like that. you know that’s still outputting nasty stuff up into, not up into 1400 hertz and higher because it’s only rolling off quite slowly. Meanwhile the horn is upset because we’re sending a lot of bass frequency to it which it doesn’t like.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: So it’s, it’s nearly at its, you know, X max and getting distorted apparently.

Andrew Hutchison: Beyond its X max and beyond judging.

Kim Ryrie: By your, in our case beyond it.

Andrew Hutchison: Diaphragms a dozen at a time.

Kim Ryrie: Flying diaphragms.

Kim Ryrie: that’s the name for a band.

00:05:00

Kim Ryrie: So anyway, so long story short, yes it is.

Andrew Hutchison: We’re talking horn diaphragm.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So, so long story short.

Andrew Hutchison: But I, but I didn’t, but it planted a seed.

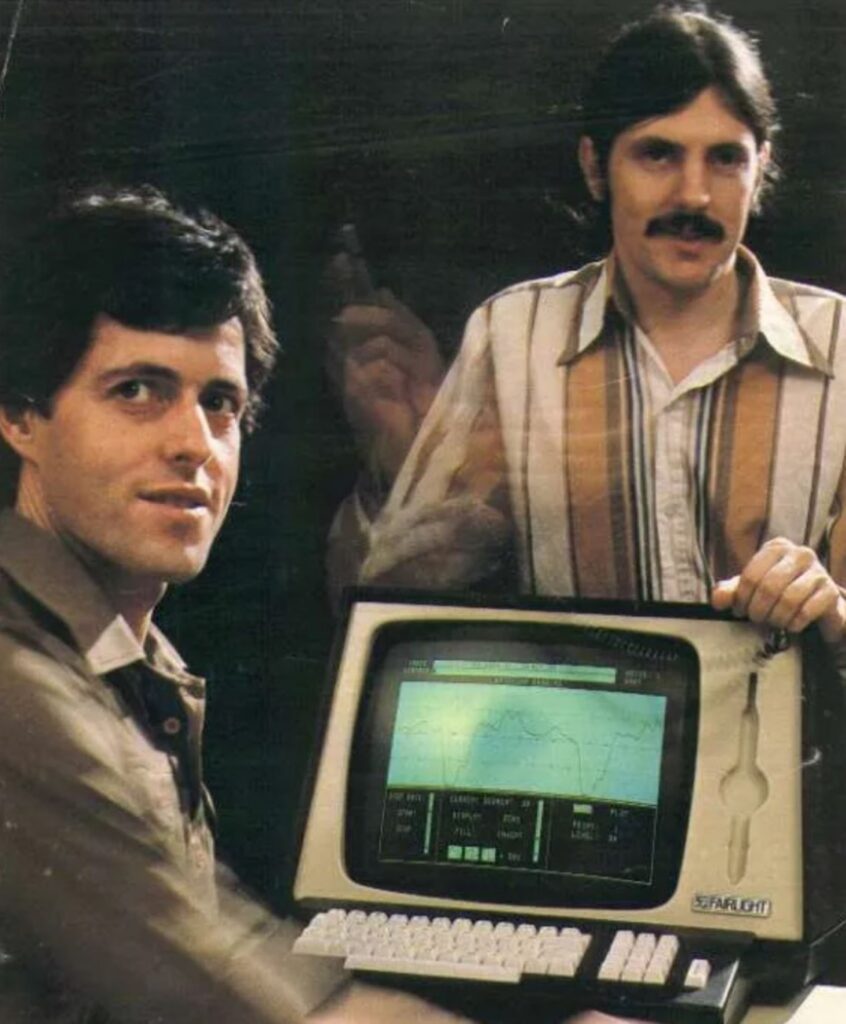

Kim Ryrie: Obviously I wasn’t involved in speakers after that because the Fairlight distraction went on for 20 years or something.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And then But in, in Fairlight I’d started using a lot of D. Another good name.

Andrew Hutchison: For a band, the Fairlight Distraction.

Kim Ryrie: But anyhow, so so you asked about how we started DEQX, which the original name was Clarity eq.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And what had happened there was one of our programmers, guy called Brian Connolly had left and started his own company called Lake DSP and Lake, had that name.

Andrew Hutchison: Rings a bell.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. Lake had come up with this headphone technology whereby they come up with some HRTFs, which is head related transfer functions, which is sort of how the ears work to Determine where sounds are coming from.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: So each ear filters in a certain way. And if you can reproduce the way the ear is filtering by actually sticking a microphone inside the ear.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Creating, you know, doing a frequency sweep, impulse sweep, I should say. you can create, ah, a filter called an FIR filter. Finite impulse.

Andrew Hutchison: Yep.

Kim Ryrie: Response filter. And you can mimic, if you just stick headphones in your head, you can mimic the sounds coming from outside of your head rather than in between the headphones. And this was this technique that Lake had working and they contacted me. I was working at Fairlight at the time and I was sort of winding down a bit at Fairlight because by then we had venture capitalists and we had lots of politics and I was getting a bit sick of it. And I bet Brian said, can you help us commercialize this, this stuff because we run out of money and need to get investment. Yeah. And so I went and heard it and I said, well, the first thing you got to do is make a little demo. So I wrote a little script with, with Q, calling James Bond into his study to point out that the Russians were trying to get hold of this technology which make headphones work outside of your head. And good Lord, Kyu, this is unbelievable. And of course you put the headphones on and you can hear this happen.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And we ran into, we made this little one minute demo of this and it landed on Paul Keating’s desk, who was the ex prime minister. And and Brian had met Paul out in the street and they had a chat, met him in the street and yeah, because that office was next door in the city. And and Brian was explaining, he got. Paul politely said, oh, what do you do? And he said, oh, we make this technology. Oh, that sounds interesting. And Brian says, would you like to hear it? So anyway, we, we sent up a little CD battery. CD player with headphones. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: Landed on Paul’s desk. And next day he was in Lake’s office saying, this is unbelievable. Hooly Dooley. This is fantastic. Hooley Dooley. And show us around. And so long story short, Paul introduced Lake to a rich friend of his who invested a million bucks or 2 million or something. Lake ended up going public. but meanwhile, I’d helped him do all this and, and I said, Brian, do you realize you could use this FIR filtering, technology for loudspeaker correction?

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: You know, you could measure a loudspeaker like we’re measuring the ear, the inside of the ear, the Inside of the ear was. All it was doing was just giving you an impulse response of what the ear was doing. Which amounts to the same thing as what a speaker’s doing the other way around.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, but in verse, effectively. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

FIR filters can correct frequency response, but they also introduce timing errors

Kim Ryrie: And which means you can look at what it’s doing wrong and create an inverse filter for that to correct those anomalies. But the amazing thing about FIR filters doesn’t just correct frequency response because everyone knows, you know, all the audio files listening know that you can change frequency response and it, yeah. Might sound a bit better or might sound a little, the tone’s a bit different, they’re all very nice. But the X factor is the timing coherence is the phase linearity of what’s going on. and what’s amazing about FIR is that you can essentially, It’s complex the way it works mathematically, but effectively what happens is that you can measure

00:10:00

Kim Ryrie: a loudspeaker’s impulse response from that. You can see the frequency groups that are actually being delayed.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: Slightly by the electromechanics of the, of each transducer, the woofer and whatever. plus the, the errors that are being introduced by the crossover filters. Because they’re not linear phase filters usually in the speaker, they’re minimum phase. So. And it will delay other people, you can make it delay other frequency groups so that these delayed frequencies can catch up. Now we’re only talking about, you know, probably three or four milliseconds through the mid range frequencies, which is where it matters. Which is where we notice timing going wrong subconsciously. We don’t. We’re so used to hearing.

Andrew Hutchison: It’s not like you can hear all that tweeter arriving late.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly. You wouldn’t have a clue what’s going on. and I’m talking about frequency is not just between drivers being out of time. I’m talking about frequencies within one driver being out of time. And so, you know, the old story is, well, sound travels one foot in a millisecond. So in three milliseconds we’re talking about three feet. And again, doesn’t sound like a lot, but we notice it subconsciously. We notice a centimeters to detect where sound is coming from.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: So our hearing is incredibly acutely aware. Yeah. I think that when stuff is wrong.

Andrew Hutchison: That’S an important point. Is that for people who not like. Oh yeah, can you hear that? Well, I mean that is sort of these phase differences are kind of how your hearing works. You’ve got to hear an ear on each side of your head for a reason. Yeah. and your brain’s measuring the, the difference in arrival times to work out where stuff’s coming from. Is that right?

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, and that’s exactly right.

Dolby bought Lake Audio and used their technology to correct loudspeakers

Andrew Hutchison: Are you looking for your tribe? Visit stereonet.com today to join one of the world’s largest online communities for hi.

Andrew Hutchison: Fi home cinema headphones and much more.

Andrew Hutchison: Read the latest news and product reviews.

Andrew Hutchison: Or check out the classifiers for the largest range of gear on sale.

Andrew Hutchison: Membership is absolutely free. So visit stereonet.com and join up today.

Kim Ryrie: Well, you can tell, right, so the head’s only, what, six inches wide?

Andrew Hutchison: Mine’s big.

Kim Ryrie: Mine might be eight inches.

Andrew Hutchison: Brad’s huge.

Kim Ryrie: So if, if something’s coming, you know, off from 45 degrees.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: The difference is only inches.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: And we’re picking that up.

Andrew Hutchison: yes, if you work out the time component.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, yeah. so we’re incredibly Microseconds.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, lots of microseconds. Not one microsecond, but yeah, I mean, we’re very sensitive.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, very sensitive to that. So, so that’s what’s amazing about this technology. And so I said to Brian, why don’t you use this? Why doesn’t Lake do loudspeaker technology? He said, well, we’re just so tied up with this headphone stuff and Dolby’s licensing it from us now. They’re going to call it Dolby Headphones and therefore we’re going to go public.

Andrew Hutchison: Paul wants to get his money back.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So that’s. And that is what happened. Paul’s mate, isn’t he? And by the way, meanwhile, they patented the way they do the FIR processing with dsp and we’d made an agreement to license their patent to do speaker correction. And so then of course I’d helped them get taken over by Dolby. Right. So Dolby take them over. long story short, they went public, but then Dolby delisted them and then bought the whole company out.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And now Lake became Dolby Australia with 200 engineers working there in the city for a period. Yeah, I think it’s down to about 100 now. But, you know, they were pretty serious.

Andrew Hutchison: In this city somewhere.

Kim Ryrie: I’m not sure where they are now, but at the time that I was dealing with this, they’re in the city.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Okay. So, but, but Dolby said, no, you can’t license our patent. I don’t want, we don’t want anyone to have this stuff.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And, my partner who’d started, Clarity EQ with Me or now called DEQX Paul Glendenning said, oh, don’t worry, I know another way to do this.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh, okay.

Kim Ryrie: I said, really? And he said this is all mind numbing arithmetic that I don’t understand. And so he, he came up with a new way of doing it. The only difference was we had to use floating point DSP arithmetic rather than the lake process. You could get away with fixed point which was cheaper to do back in the day with dsp. So that was our only slight compromise. We ended up patenting our version of it. We had a US patent on that. And so that’s what we’ve been using ever since. So effectively what we’re doing is we can. Well, as you know, as a speaker designer, it’s not just that designing speakers is a whole shopping list of dramas.

Andrew Hutchison: Certainly is a really good way of.

Kim Ryrie: Putting a shopping list of

00:15:00

Kim Ryrie: dramas.

Andrew Hutchison: Say it more kindly and say it’s a grab bag full of compromises or something.

Kim Ryrie: Okay, let’s leave it at that. But going active resolves a lot of those issues, right? So for instance, one issue even going active, you know, the pro speakers, as you say, have been active for many decades, but they started off being analog active. So they were just using 24 decibels nearly universally. 24 decibels per octave. you know, crossover at 2K for the tweeter, whatever. Maybe they were three way, so there’d be 200 hertz to the woofer. but even they weren’t time aligned. Right. Because what, what Pro Audio wanted was an accurate frequency response. They didn’t really care about time alignment because what they had to be sure of is that when they were mixing stuff.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: They just had the levels of everything accurate.

Andrew Hutchison: Right.

Kim Ryrie: So they were totally fixated. Fixated, yes, on an accurate frequency response so that they knew that what went out the door was at least mixed m and balanced properly.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And then they’d leave it to audio files to get their own speakers that cleaned up timing issues or whatever Audio files needed. Well, that’s right.

Andrew Hutchison: I mean they’re only listening to it. It’s not like it’s part of the recording process in the sense that it’s laid down or fixed in the recording. So yeah, you can.

Kim Ryrie: That’s true.

Andrew Hutchison: The customer can fix it at home with their Wilson audios and their adjustable mids and tweens. Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: If they’ve got a spare 50 grand US, you know.

DSP came along for studios for active, uh, speakers

So anyway, then DSP came along for studios for active, speakers. And the beauty of DSP meant you could, first of all, you could go to steeper crossovers if you want, pretty easily. even doing steeper than, 24 decibels per octave. Filters in the analog world wasn’t all that easy.

Andrew Hutchison: No, no.

Kim Ryrie: You’d have to really be selecting components and measuring everything. It was a bit of a pain.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Virtually impossible. Passive speakers.

Andrew Hutchison: yeah, I don’t think anyone’s really explored that with a passive filter, but. Brad, have you done a sixth, order passive filter?

Kim Ryrie: I’m sure he has.

Kim Ryrie: No comment.

Andrew Hutchison: No comment.

Kim Ryrie: How that turned out. No.

Andrew Hutchison: So, no, no, it doesn’t.

Kim Ryrie: It, it’s not fun.

Andrew Hutchison: Doesn’t. It doesn’t, doesn’t roll off accurately.

Kim Ryrie: It’s not fun and it’s not easy.

Andrew Hutchison: Creates its own problems when you’ve got.

Kim Ryrie: Capacitors with typically 20 tolerance.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh, no, you’re definitely. Well, your hand. Any passive filter, your hand selected components. I mean, we batch everything up here because otherwise you simply won’t be building two matching crossovers for a stereo pair of speakers. It won’t happen.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly.

Andrew Hutchison: So, you’ve got. So the DEQX product started and of course.

Kim Ryrie: Let me just finish that. Just saying. When DSP came in, what they could then do was delay. At least they could time alarm. At least they could then time alarm drivers and they could do simple parametric eq. So if they had a bit of a peak somewhere or a dip somewhere, they could tweak it to get the frequency response better. So at least that fixed time alignment issues between drivers. Not within the driver, but between. So then when we came along, with fir, we’re thinking, well, hang on, we can now do linear phase crossovers because that’s what FIR lets you do at any, slope. So in the analog world, if you want linear phase, you’re pretty much stuck to a capacitor.

Kim Ryrie: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: Single pole.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And if once you go beyond that, you no longer, linear phase. So with our version of fir, processing, we can do steep linear phase. We can do. Typically at the show we just did, we had 12 pole filter. That’s 72 dB active.

Andrew Hutchison: Wow. Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And which means it’s just virtually a brick wal do. Which means there’s just no crossover. Even if it sounds all right.

Andrew Hutchison: Like it doesn’t.

Kim Ryrie: It’s, it’s counterintuitive. But it sounds amazing.

Andrew Hutchison: Which it kind of should sound amazing because, I mean, you can, I mean you get the best out of your drum.

Kim Ryrie: I used to. You can’t do that. You got to Have a bit of a cross bit of, you know, melding an amalgam. And you obviously can, you can set with our system any crossover thing. You can do 48 decibels or 36 or whatever.

Kim Ryrie: Right.

Kim Ryrie: but, but we, but with that particular design we did at the show, we chose 72 decibels.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And so and then within each driver we, we can correct any non linearities within the driver itself. Just. Right. Okay. So

00:20:00

Kim Ryrie: you end up getting very consistent timing coherence. We’re only adding milliseconds to the audio, which no one doesn’t care. The only time it matters is if you’re trying to synchronize with the video, but you can get away with about a 15 millisecond delay before video starts seeming to be out of sync with the audio. so that was, you know, that’s the bottom line of the advantage of going active.

You got rid of your passive crossover and you’ve got no cable

there’s other advantages that we talked about which are inherent to any active system. One is that each amplifier is bolted directly to each beaker diaphragm. You know, so not only have.

Andrew Hutchison: You got rid of your passive crossover, you’ve got rid of cable as well.

Kim Ryrie: You got rid of cable not necessarily because you might have the amps m externally, but what you do have, but.

Andrew Hutchison: You’Ve got a foot of cable not you know, well, a foot or.

Kim Ryrie: Even if you’ve got lots of feet, what you have done is you’ve, you’ve only got three or four octaves worth of audio running in each cable.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: You haven’t got ten octaves.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes, indeed.

Kim Ryrie: Fighting amongst each other, you know, in a single cable. You’ve also got each amplifier only having to deal with three or four octaves.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: You know you’ve got a, you got a, a high current amp for your base.

Andrew Hutchison: Indeed. Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: You’ve got something for the mid range and you could have a 10 watt class A for your tweeter if you want. So yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: So the advantages are, the advantages are ah, clear and they’re immense and yet still in the audio, in the hi fi industry, the concept of a, of a, an active speaker is kind of shunned a little bit by, by customers and dealers. people are a little bit scared of it. Why? Why? I don’t know. Because ultimately just plug them into the wall like a vacuum cleaner and connect up a cable to the back of almost any preamp. Preamp obviously. But any avm, any, just about any audio integrated amp has a pre out pair of RCA sockets these days. I don’t know what the problem is. M It’s a weird thing I guess it doesn’t enable easy comparison between passive speakers and active speakers where the passive speaker has obviously got its own power amp and you know, there’s the saga of, you know, how are we going to compare one with the other and of course probably shouldn’t because the active speaker is immediately in most cases going to sound more correct obviously. But what, how does your product get used? So your customers, of which you have many, you’ve been selling these things for a long time in their initial versions and now you’ve got this new super duper version that’s almost finished beta testing. As I understand it. As far as the software is concerned, it’s a beautiful looking product. I’ve seen it being built, parts that are inside it. This is clearly genuinely high end electronics in every way. It’s not some fake high end thing that’s got a pretty case and just garbage china spec insides. This is a serious product. Lots of processing power but also lots of high quality audio, capability. But how does someone use the product? How do you. Or what, what is the main use? Like are they using it with their home built speakers or are they using existing high quality speakers? Pair of Wilsons maybe?

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, just tell us about that. It’s a really good question. So that’s why we have three different models.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: So the flagship model, which we call the pre8 because it’s got 8 outputs but that only means that it’s still stereo but you can have outputs for subwoofers, outputs for bass drivers, output for mid range drivers and outputs for tweeters, all of which would then go to their own amplifiers. Yeah, which then go to the, to the drivers. To the drivers. So that of course implies some degree of diy.

Andrew Hutchison: So it kind of does.

Kim Ryrie: You can’t just go into your hi fi shop and kind of. Can I have that box and there’s a pair of connectors on the back for each driver with nothing in between. So it does imply that you’re going to have to do that yourself. Unless and, and that’s what most of our users do. They do do that. They, they will either go and buy an affordable speaker of any kind, they will take the crosshair out and they will bypass their internal.

Andrew Hutchison: So this is a question I’ve been meaning to ask you for a long time. So that is, is that what some customers doing that if they want a pretty box like they want Something that their partner is happy with.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Are they doing just that? Are they going getting a pair of, I don’t know, a pair of 800 series BMWs. And someone will have done this, I’m sure, and take that hefty passive crossover board out of the bottom of the box and

00:25:00

Andrew Hutchison: wire up all the drivers to extra terminals on the back, then via your suggested or their power amps to your DEQX box. Is that. Has that happened?

Kim Ryrie: Totally, it’s happened. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay. On 800 series, I’m using as an example. But certainly they’re getting. They’re getting production quality speakers and kind of getting rid of the bits they don’t need. Yeah. Bypass. Much easier way and simpler way to describe it. Thank you, Brad.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, sorry. Well, well, look, if you just paid, you know, I think I was just looking at an ad for Wilson Audio. Talking of Wilson Audio, is the like $50,000? Yes. you would think twice before you started ripping them to pieces.

Kim Ryrie: perhaps you might leave the crossover in situ, Just disconnect the cables.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, I don’t know where the crossover is, but I know it’s probably potted in a fancy box and it’s bolted down somewhere and there’s lots of heavy cables running to the drivers.

Kim Ryrie: So. Yeah, look, I can’t speak for that particular model of speaker, but. But the point is you don’t. That’s the idea is that you don’t need to pay $50,000 for a pair of speakers. That’s. That’s our hope. But if you’ve already got them and you’re thinking, you know, you feel like an adventure, you know, you can do it and you can do it without wrecking them. You know, you can, you can take things apart in a way that you could put it back together again if you ever want to resell it. But in fact, we’ve just introduced, some amplifier amplifiers for particularly for people that want to go active, because suddenly you need, say, three channels of amplifier per speaker. you know, and then often you might have subwoofers, but they’ll already be active, so you don’t really need four amps. So we’ve done a thing we call. We’ve got. The model we had at the show is called AMPI3 and it’s got three. as you know, we’ve been freaking around with D class amps, mainly because for us, we can deal with D class. Everything else is much more complicated and you can buy amps from millions of places. But for us, we were really impressed with the new Purify line of amplifiers. So the Ampi 3 has three purify modules in it and a power supply and it’s this. And the metalwork is designed that you can actually bolt it to the side of a speaker.

Andrew Hutchison: It looks like you could do just that.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. so you can take out the plate that is holding the existing say bi wireable connectors. Literally take the whole thing out. Then you put a rubber seal around where you then bolt the thing so you keep the, the box airtight. And you can then just wire directly to the, to the speaker so that.

Andrew Hutchison: Where the terminal cup was becomes your port for getting you three lots of cable in there.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: That goes straight into the amp.

Andrew Hutchison: Say you, you, you. You’re pulling the speaker up. I mean if you do that to a production speaker you, you’re really not destroying it to

Kim Ryrie: No you’re not. You can put that back later.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: You probably get it. Maybe the average consumer might get a table to give them a hand.

Kim Ryrie: You will probably have to put about four screws into the, into the timber work to hold the at the back.

Andrew Hutchison: Can you blue tack it on double sided tape? Actually being class D, they probably don’t weigh that much do.

Kim Ryrie: Oh they don’t weigh much at all. No.

Andrew Hutchison: You could double sided tape.

Kim Ryrie: No, they’re just quite small but also quite small screws and.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And that. That would be the only downside. so I would imagine if they’re committed.

Kim Ryrie: They’re committed to.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly. Once you’ve done it you’re not going to be going back.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: That’s for sure.

Andrew Hutchison: Because it sounds obviously the, the sound is amazing. So, so just. So that’s one kind of buyer for a deck.

Kim Ryrie: But of course you know you can go to Harvey nor you can go into anywhere. Buy a floor standard of almost any kind.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: That costs a couple of grand.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Pair and you can easily do it to that and you’ll get a pretty startling result. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: You know.

One way you suggest Brad is you don’t change the speaker. You don’t make it active

Kim Ryrie: So let’s now call line up what you can do. One, you could take a high end. What they call high end loudspeaker. and take the DEQX and basically either design your own crossover filters.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: With those drive units or just simply correct it for free frequency and group delay.

Kim Ryrie: Yes.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: That’s not, not, not changing the passive.

Kim Ryrie: No, you don’t have to do that. And, and as you know.

Andrew Hutchison: You know so just, just for clarity. So The other way you’re suggesting Brad is you don’t change the speaker. You don’t make it active. You use the power of the DEQX to fix the issues that are inherent in the passive.

Kim Ryrie: That’s right.

Andrew Hutchison: The way that the production speaker. And two, you don’t modify, you just connect it up. Use the DEQX as your preamp.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Twiddle some knobs. Well, run a measurement. No doubt with the M. With the mic.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly. And two of the three models we have now are exactly for

00:30:00

Kim Ryrie: that. They’re not intended to go fully active. They do let you do biamping because a lot of say floor standards and even bookshelves let you bi- wire them. You’re still going through their internal passive crossover. So you can’t change the crossover frequency that they’ve. But you can make them steeper. You can put another crossover on top of the

Andrew Hutchison: Over the top.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. And typically you’ll only be doing that. See typically inside of, let’s say you’ve got a three way bi wirable speaker. The bottom connector will be bass.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And the upper one will be mid and tweed.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: So which has another advantage is that it makes it easy to measure the mid and tweeter together, without the bass involved. You can do that separately now with the DEQX. So you can use four channels of amps.

Andrew Hutchison: Yep.

Kim Ryrie: You know, one driving the. The upper.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: I mean for left and right.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And so that’s, that’s what you can do with the pre-4 model which is basically intended for a full range speaker, plus subwoofers or for bi wiring, bi amping, existing bi wireable speed. And that’s most of the market at the moment. You know, but for people that really want to go the whole hog, you know, I’d recommend you get the flagship model. You can start off doing that with passive speaking.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: But you know, a year or two down the road you might feel like, well, let’s try. Or you find an old pair of speakers on ebay or something. Ah. You know, a pair of classics. For a pair of classics.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And get into them newly some life.

DEQX software tells you how to measure the speaker rather than a room measurement

And see now what comes with the DEQX, which works with all three models is our software, which is the key to what we do. So it’s all integrated so that you measure the speaker in a certain way. it tells you how to measure the speaker because it’s different from a room measurement. Okay. A room measurement you measure around the sweet spot where you’re going to be listening. Whereas a speaker measurement you want to be at least largely anechoic. You don’t Want much room information in the measurement. It doesn’t matter having some room reflections in the measurement. there’s ways we suggest you’ll do a sort of partially near field measurement. Doesn’t matter that there’s a few reflections from the floor and whatever. you’ll tend to do it off axis to the speaker. You’ll do it, you might say point the speakers straight into the room rather than towing them in and you might measure them towards where the sweet spot is. In other words, you might have the microphone back, say 60cm, something like that from the baffle and then at about.

Andrew Hutchison: 15 degrees or something, something like that.

Kim Ryrie: Back to the midpoint where you might be sitting.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly. Because that’ll just give you a very clean phase accurate measurement of what the speaker is doing natively. And we need to know that to be able to compensate for that.

Andrew Hutchison: And then you gate that measurement internally. Like in the.

Kim Ryrie: And then. Yeah, internally. The software deals with, to make it.

Andrew Hutchison: Sort of a quasi anechoic measurement.

Kim Ryrie: If you’re measuring the close. You don’t even need to gate it much.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: If at all.

Kim Ryrie: Midway between the tweet and if it’s a two way try and get that.

Kim Ryrie: Crossover stitch up and it’s very easy. And by the way, we have an online support thing which comes with for free for people in the beta program which we have at the moment. we get online with them, we can run them through the software. They don’t need to understand what’s going, going on. No, no, no, it’s all pretty.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, that’s. I think that’s what I’m. The point I’m trying to make is that both my own interest to understand who is likely to want to. Because the product’s amazing but it is quite, it is clearly designed by a very smart team of people for very smart customers is what it seems. But meaning, that.

Kim Ryrie: No, not.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, but that’s technically savvy.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, they’re technically savvy. They want to come through the back door.

Kim Ryrie: Do they need to be and get.

Kim Ryrie: No, they used to need to be. All our, all our legacy products were a nightmare to use.

Andrew Hutchison: just, just, just so you know.

Kim Ryrie: We had, we had news flash of it but you know it has 160 page manual.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: And

00:35:00

Andrew Hutchison: so you’ve simplified it because we’re on version four now.

Kim Ryrie: Right. Yeah. The whole point of generation four is we, we took the software off Windows. Ah. it’s now all up in the cloud. Which means. Yeah, you can, you can run it from your iPhone. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: You shouldn’t. Not for setup, but, for setup, you should use a real computer. If you can just. On a browser.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And it’ll show. Because that’ll show you the graph. You want to see what’s going on. You don’t need to see them. We can do that online with you. We can make all the decisions. And that’s a free service for people that are setting up. or dealers will do it.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Or anyone that’s even remotely savvy can do it. And the idea of the beta software program we’re in now is just to get that down to the simplest possible user interface we can. Doesn’t, mean that if you know what you’re doing, you can’t get under the hood and be tweaking stuff. But for 90% of what people need.

Kim Ryrie: We can deform so effectively, you’ve got a DEQX, which will just. You bung a pair of speakers on.

Kim Ryrie: And that’s it. You don’t. For those who love the look, the sound.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. You don’t have to even use any correction. Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: You’ve got all the.

Andrew Hutchison: No.

You should have the mic at least for doing room measurement

And that’s my next question. yeah.

Kim Ryrie: So that’s the first level, in a sense. Sorry.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, yeah, because so someone who just wants a very good quality preamp processor. Oh, well, it is a processor. Not surround sound processor. Dac, but yeah. DAC streamer. A beautiful product that. That’s just beautifully crafted. sounds great. They just want that they can just buy a nice pair of speakers that they like the sound of at the shop.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: They can only make them sound better by. That’s getting out the measurement microphone and, and letting the. Letting the DEQX interpret what it’s hearing and then make some corrections. Yeah, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Question then. So when you buy that, what m. Might. Might call. I don’t like using the term entry level just. But you do get the microphone with that, even if you’re not going to utilize.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. Because you. You should have the mic at least for doing room measurement. Right. And at least just see if you’ve got room. Correction. Huge room. Room issue. You don’t really know where it is. So he’s.

Andrew Hutchison: That’s right. So, sorry, I didn’t mean to cut you off, Kim, but there’s part two, because I do sort of want to for my own benefit. But for the listener, was saying, we’ve got a DEQX. We’re doing this. But it’s got such a broad range of skills. The other thing of course it does. Is so you take your normal. You like a pair of, I don’t know, focal something or others or B and W something or others or a pair of Dynaudios or Dellichords or whatever. They don’t need any correction. so you’ve got.

Kim Ryrie: Sorry, that was really Dare you.

Kim Ryrie: I didn’t even have that.

Andrew Hutchison: So you’ve got this.

Kim Ryrie: I’m assuming that’s the case.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, we won’t know until we turn the DEQX on. But the point is you’ve. But you’ve put your Dellichords in a room that’s not particularly favorable. The DEQX like it’s all glass and tiles. You live on the river in Queensland. The wind’s blowing through. You don’t want to lock yourself in a, in a correctly, treated space. can the DEQX also deal with that glass and tile emporium, affect the deck extra reverb time that. Because, I mean you can’t get rid of the reverb time. But does it do a bit of like. It is room correction on the DEQX. A separate thing. That’s a separate mode. We’re going to test for room. Because you are. Because you’re going to put the mic like you said, over, the listing position.

Kim Ryrie: It is a separate thing.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And or, or you can, let’s say you’ve got a bi wireable speaker.

Kim Ryrie: And as we were saying, you’ve got one amp driving the mid and the tweeter and you’ve got the other amp doing the bass. Well, the bass is almost certainly crossing over to the mid. Somewhere around 200 hertz. Right. Somewhere like that. And the room as you know, is all about below 200 hertz. Pretty much.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. Except when you have glass.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, well, yeah, I mean, I’m giving you the worst, worst, worst possible case. But, but yes, far as the massive room modes. Yes. They’re under 200.

Kim Ryrie: So you can just do, you could, you could do that bass correction by measuring from the listening position.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah. Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And effectively not doing a speaker correction on the bass per se. Because it’s all about room and bass at the, at the listening position.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: so you can, you can do a separate filter which will do that. They have to do it again if you go to a different room. Yeah, sure. But yeah, you can do all that. You can.

Andrew Hutchison: It’ll do a lot.

Kim Ryrie: You can just do different things.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

You can control the software for them remotely if they want us to

Kim Ryrie: It’s why we have the DEQXpert, we call them the DEQX.

Kim Ryrie: Back to ask about the DEQXpert.

Kim Ryrie: Because People often don’t know what all

00:40:00

Kim Ryrie: the options are. And, and it will depend on what their circumstances, what their system is and what their room is like and everything. So in minutes we can see what’s going on and make some recommendations and m. We can control the software for them remotely if they want us to.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, that’s what I’m thinking. Yes. So you can. Look, their machine is connected to their Internet connection.

Kim Ryrie: Yes.

Andrew Hutchison: And you can. And the correction, files or what have you stored in the cloud.

Kim Ryrie: We would tend to use, two communication things. One is the, we would not actually connect via their connection to the Internet to their box. Typically we can do that in the future, but we would tend to run a separate, connection via TeamViewer, whereby we can literally control running it on. And we can visually see you’ve got.

Andrew Hutchison: Your fingers on the button.

Kim Ryrie: So, yeah, we visually see the room and where they’ve put the microphone and we say, no, can you move the mic a bit to the left or can you come out a bit further? And so that’s the way.

Andrew Hutchison: That’s pretty effective. That’s cool.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So, and it gives us a very good idea. And then we see the measurements they get. And we got a very good idea just by looking at the measurements, what it’s going to be sounding like a quick question then. Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Do you often get them to play around with speaker positioning or is the whole. Is the whole point of the correction is to. I’m just. I have to plonk them there because.

Kim Ryrie: The wife has already decided where the speakers are going or the man. So.

Kim Ryrie: So if it’s.

Andrew Hutchison: It’s not.

Kim Ryrie: If it’s.

Andrew Hutchison: Let’s call it something for adjustment. Okay.

Kim Ryrie: So it’s.

Andrew Hutchison: Let’s call it. As Kim says, they’re already in the correct spot.

Kim Ryrie: Right.

Kim Ryrie: Okay. So therefore, that’s where the DEQX comes to the four.

Kim Ryrie: If there’s an option, if you’ve got a room dedicated. Absolutely.

Kim Ryrie: You can.

Kim Ryrie: We do the formulas and we tell you where the best spot.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. Okay.

Kim Ryrie: Position is. Okay. We’ve got that flexibility, but usually that’s not an option.

Kim Ryrie: Okay. Okay.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay. But what I’d like to do is have a quick break. I want to come back and ask you about, I mean, obviously your history is in Australia, but I don’t want to ask you about the fact of, why they’re made here. So we’ll be back shortly.

Lindemann LimeTree hi fi essentials enhance any hi Fi system

Andrew Hutchison: I was chatting with Jeff at HeyNow HiFi this week, and I asked him, you know, what was happening.

Andrew Hutchison: In the store he said he had a cool bargain, really cool that the not an audiophile listeners might find interesting. Lindemann LimeTree hi fi essentials. German made, compact, high end discrete components that enhance any hi Fi system. He has a music streamer. Music streamer with a DAC and a phono preamplifier all on special. Why don’t you head to hey now hi fi.com and search lime tree.

Kim Ryrie: The vast majority of the parts are assembled in Australia

Andrew Hutchison: And we’re back. We’re back folks. Back with Kim Ryrie, at the desk with Brad Serhan and myself. to discuss the remainder of the fine detail of the DEQX generation for. Do you call it a preamp DAC or are you calling it a streamer DAC preamp or you just call or a DSP processor because it can be used in all these different ways. What do you call it?

Kim Ryrie: I don’t know what to call it.

Andrew Hutchison: This is the problem. It does too much.

Kim Ryrie: Well, some people have called it like the Swiss army knife of audio.

Andrew Hutchison: Well that’s kind of what it is.

Kim Ryrie: Well as you say. Well it’s, it’s an integrated. I suppose that’s the best way to say it. It’s an integrated. Well no, only one model has an amp. Yeah, but, but fundamentally it’s a preamp. I guess it’s got lots of digital and analog inputs. It’s a streamer Y. it’s. It’s got high end pro end DEQX in it. state of the art DEQX. It’s got state of the art A to D so that we’ve got. And of course Dynavector, wouldn’t have made a custom Dynavector preamp for us unless they were happy with the transparency of the digital. And it’s totally transparent.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: We’re talking about minus 240db distortion in the digital domain.

Andrew Hutchison: Is that right? Okay.

Kim Ryrie: in other words it’s beyond non existent. The distortion that there is comes in when you go back into the analog domain.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: From the, from the DEQX and so on.

Andrew Hutchison: So you now it, it’s all made. The vast majority of the product of the parts is sourced in Australia and it’s all assembled here. What’s designed here? I mean.

Kim Ryrie: Well, no, I don’t think that’s fair to say. The electronics pretty much all come from overseas. I don’t mean, I mean the chips. Right.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Australia make zero chips.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, we don’t. I don’t think we’re making any reels of surface

00:45:00

Andrew Hutchison: mount resistors either. So. So. Yeah, no, that’s a. That’s right. I guess none, of it’s made here. I guess there’s an awful lot of assembly happening here.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, it’s awfully.

Andrew Hutchison: A lot of, A lot of the parts are, important. Of course.

Kim Ryrie: And it’s all designed here.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, but it’s designed here. And is it designed here? I mean, your team of people are mostly Australian.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, it’s all designed. We’re incredibly lucky. I think, you know, over the years that’s where I have been lucky, has been to work with great people.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: And we. For instance, Joe Narai, who’s our COO and RD manager, he and I used to compete in the old days selling digital audio, workstations to America.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, right.

Kim Ryrie: He sold hundreds of his dsp, consoles and stuff. And we’ve always been friends. But you know, it’s interesting that the two, the two digital audio workstations the world was buying, both came from Australia from completely separate companies.

Andrew Hutchison: And now you’re working together.

Kim Ryrie: And now Joe’s just joined us. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: this year. And I’ve been trying to get him for a while actually, but I’m getting old. I know. I was gonna say he actually needs someone.

Andrew Hutchison: He looks, he looks younger.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, he is younger. we’ve got Glenn Dickens now. Glenn was running R D at Dolby for 15 years.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: he’s. He virtually co invented Atmos at Dolby. He’s now working for us as we speak. He’s in the room next door. Yeah. on the blower with Joe.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: trying to sort out a time alignment issue in the base integration algorithm.

Andrew Hutchison: So the pedigree.

Kim Ryrie: So we’ve got some pretty heavy hitters.

Andrew Hutchison: Absolutely.

Kim Ryrie: In there.

Kim Ryrie: Chris Alfred worked with me back in the fairlight days. there he was working on the the daw. We got an Academy Award, technical award.

Christoph was co creator of Dolby Atmos

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: Chris went up to get. He’s got the little golden thing.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh really?

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. For services to the film industry.

Andrew Hutchison: Where’s that? Is this that in the building?

Kim Ryrie: No, that’s at Chris’s house. And what a touch. so we’ve been working together for ages. Christoph. also running Dolby. He was co creator of Dolby Atmos. He’s now, with us as well. Not full time, but as a. Pretty much as a full time consultant.

Andrew Hutchison: so you’ve absolutely got the people you need to make this very complex product work.

Kim Ryrie: That’s right. And Now, Glenn, who I mentioned, he’s on 120 patents.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh, okay.

Kim Ryrie: Not many people are like 120. Yeah, he’s the guy who, with Dave McGrath back in the lake days, come up with the first fir pattern.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: You know, which is what’s made all this stuff even possible.

What’s with Australia and, um, digital processing? It’s, it’s

Andrew Hutchison: So what’s with Australia and, digital processing?

Kim Ryrie: It’s, it’s really an interesting question.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And I don’t know the answer to that. And of course, Tony Furse, who was the guy that designed the original Fairlight dual processor stuff.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: You know, he’s Australian. He’s very Australian. he used to throw boards across the room at me when, I. Well, actually, I should have told you this story. When we started working with Tony, you know, we took over his prototypes and we were making our own printed circuit boards of his stuff and we took it over to his place and he plugged it into his machine and it blew up. And of course we had the polarizing key slightly out of center. Oh, the circuit board, there was like 200 connections on it.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And so he picks the border out of the machine, throws it across the room. Peter and I says, if you guys don’t get your act together, you better, you better forget about getting in business. So that was the equivalent of the.

Kim Ryrie: Zap he almost got.

Kim Ryrie: Really. So, Tony was a character genius. And so we’ve just been, you know, we’ve just been really lucky to have people like that. People like Michael Carlos, who, as I mentioned, you know, he designed the page R, Ah, music sequencer, because he was a music composer. And that was what, to the Fairlight was like what VisiCalc was to Apple. The first spreadsheet. Apples didn’t take off until spreadsheets existed.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And, for us, that was like Page R, you know, the rhythm sequencer, the real time sequencer, and stuff like that. So, yeah, we’ve just had a lot of great people, inventing products before.

Andrew Hutchison: They actually exist in the sense of. Because you mentioned the MIDI thing, you know, where you didn’t invent midi, but the, the concept, you know, you were already doing it at the Fairlight. There seems like there’s a lot of that. So maybe the DEQX is slightly ahead of its, its time.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, look,

00:50:00

Kim Ryrie: it is ahead of its time in the sense that audio has to go this way. It cannot not do this because if it’s going to keep improving, this is the only way to improve.

Andrew Hutchison: It’s a bit stuck at the moment and it feels like, yeah, you’re right.

Kim Ryrie: It’S stuck because of the traditional hi fi marketing regime where you had to be able to swap components. You have to be able to just have a speaker that’s compatible with his amplifier, this amplifier.

Andrew Hutchison: The art of system building or matching system synergy. And I look, I don’t see that going away in the same way as tubes haven’t gone away and books haven’t gone away and haven’t gone away.

Kim Ryrie: But it won’t go away at the, at the, at the high end.

Andrew Hutchison: No, no.

Kim Ryrie: Where people want to experiment and do that. And that’s why we’ve got, you know, the Pre 8 and the Pre 4, where you can choose your own amplifiers and you can do all that, whereas normally an active speaker, that’s all been decided for you in advance, you know. And it’s why audiophiles don’t like a lot of traditional active speakers. No, one way, one reason was what we were talking about, that the focus for active speakers for pro audio, is to get the frequency response right.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: They don’t care too much about the time to be. They just need the balance to be.

Andrew Hutchison: I can, I can see a time when, you know, an active speaker is both affordable and quite stunning in its performance. And it’ll be that performance that will take some people over the edge. They’ll go, wow, that, that. I love the charm factor of my system, but this is, this is stunning. This is. Well, you’re getting to and, and the sense of space and all of the things that they want. They get a little bit of slightly furry with their existing system. It’s a bit of fun. But the digital thing will really. I mean sometimes you, you sort of, it’s like modern cars, right? You sort of. I mean everyone loves an older car for style and the sound, but I tell you what, I mean, a modern car is just, it just works and it works so well.

Kim Ryrie: It is amazing really. We’ve got a Tesla and, and I’ve got a Toyota, right?

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: The thing I hate about the Toyota is having to get it serviced. Tesla, you don’t service them, they just sort of go forever and there’s, I don’t know what, you know, one day the wheels are going to fall off or something.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh, catch fire, that’s fine.

Kim Ryrie: Hasn’t caught fire yet. Under the command of.

Andrew Hutchison: They really, they really do if, at all. But no, I’ll tell you another story. It’s just that also the Tesla is so, it’s the tipping point For a lot of people that love cars, a lot of people that love performance cars and you know, great sound and great handling cars have had their head turned by the Tesla.

The DEQX Generation 4 isn’t actually really out yet, is it

Maybe your DEQX product is, is possibly that, that, that thing where people start, people who really love great audio systems could be tipped the other way because yours isn’t. The Generation 4 isn’t actually really out yet, is it? And this is something we should talk about.

Kim Ryrie: It’s not formally out like.

Andrew Hutchison: It’S on beta software.

Kim Ryrie: It’s, it’s. We’re running beta software because we want to just keep improving the user interface. At the moment it’s pretty easy to use. but we’re, we’re making it better.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay, so that’s, so that’s what that’s about.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. And until, and we’ve set ourselves probably the end of Q1 to have that finished. But once we get to that point, we have to sell the system through traditional dealer networks and international distributors and they get very expensive doing that. So at the moment with our beta users, with our beta members, we’re able to sell direct factory.

Andrew Hutchison: So people can ring you up. like we’ll obviously have your website, linked to from our website. People who go through the DEQX website and basically just buy the product directly from you. At the moment.

Kim Ryrie: At the moment.

Andrew Hutchison: For the moment.

Kim Ryrie: For the moment, while it’s still in business. I think we’ve only got another 70, units allocated, so I don’t know how long that’ll last. But, but yeah, the, at the moment, you can get them at basically wholesale price.

Andrew Hutchison: Wow. Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And the software you get, over virtually every month we have a sort of new software release. It’s a bit like a Tesla and you know, over the air software. and but by the end of Q1 I think we’ll be going formally released.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay, so this is a little sweet, little, A little place in time at the moment where you’ve developed this amazing product. The software is basically done. It’s been developed over the last, well no doubt years, but it’s been. People have had their gen 4 units for a while. 6, 8, 10 months, whatever. the software’s much improved over that time with the assistance of the feedback from those users. And I guess that’s part of the package deal is that you get, you get a better price because you’re

00:55:00

Andrew Hutchison: part of the R D team to some degree.

The hardware is largely done at this stage, but the software is still improving

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So we like to hear from our users, our beta users. They well, not so much the.

Andrew Hutchison: Research, but the development part.

Kim Ryrie: To give you an idea, one of our earliest. Well, one of our users is Greg Timbers. I don’t know if you’ve heard of him, but Greg was running name rings a Bell at JBL. He was a lead designer at JBL for 20 years.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Right here.

Kim Ryrie: And he retired a couple some years ago. A couple years ago. And he’s famous in the industry and he m. has, has had our traditional models, the HDP4. He had a couple of those. They could only do three way active and he needed four way okay for his system that he’s got at home, which was his own Everest jbl. And he said, you know, until I got them I could never achieve what I wanted.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Because they were passive speakers. So so anyway, so we thought I better give Craig one of our early beating units. So we gave him one of the early pre 8. But the software was just a basket case and you know.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, you didn’t give it to him, right?

Kim Ryrie: Well I shouldn’t have done it because poor. The trouble is Greg is so amazing. He, he spent a whole weekend trying to deal with the bugs in the software.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And, and he doesn’t tell you about it until later. He says oh by the way, there’s a few problems here. And he’d written this sort of 80 page manual on how to fix it.

Andrew Hutchison: Or what his complaints are.

Kim Ryrie: But no, he was just saying oh look, you know, so we, we, we got, we worked with them over the next couple of months and then they were about. Took about three software releases before we got it all.

Andrew Hutchison: Shook the basics out of it.

Kim Ryrie: But what he did say, he said but the, but the new hardware makes the old system sound broken.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh, is that right? Yeah. So there was a sound quality improvement.

Kim Ryrie: Over your previous improvement just in the. And that’s why we spent so long doing the hardware. Yeah. Okay. The hardware we have now is our third revision of Gen4. So we never released the first and the second revisions.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: But all the beta units got the.

Andrew Hutchison: All the latest versions.

Kim Ryrie: All the latest. So that’s production hardware. So that’s why you know it’s, it’s a, it’s a pretty good deal to get the.

Andrew Hutchison: Sounds like an exceptional deal. yeah, I think anyone who’s interested in, you know, what the hell this thing is.

Kim Ryrie: Well the catch is they got to buy it direct from the factory so they’re dealing with dealers and stuff.

Andrew Hutchison: But I mean for some people that.

Andrew Hutchison: Won’T be a problem.

Andrew Hutchison: I think they’ll like, yeah, I’m happy to deal with the factory. Clearly the talent is there. They know what they’re doing. So, So, yeah, get in touch. you probably won’t get Kim on the phone, but, you might.

Kim Ryrie: You never know.

Andrew Hutchison: But yeah, I mean, and the fact of the matter is.

Kim Ryrie: God help you if you do.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, could be a long conversation. The, the fact of the matter is that the, the software is largely done at this stage. It’s. It’s just the tinkering around the edges that’s left.

Kim Ryrie: I mean, you basically turn it on. We’re still doing a lot of software, but the software at the moment does work. But the new software will just simplify things.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, you’ll always be improving. And I mean all of those, even just the streaming functionality will always. There’ll always be some kind of, you know, firmware update for that, I guess.

Serhan Swift Bespoke loudspeakers designed and built in Australia

Kim Ryrie: So the good news is, though, Andrew, I think, and not just on the horizon.

Andrew Hutchison: So we’ve got a good news story.

Kim Ryrie: We have a good news story and, breaking here today is that if I decided, if I decide to buy one today, Kim. Yeah, And I don’t really want it. I, just want to reiterate. I don’t want to really play around with the. All the other, you know, what is it called? The thingamajig. And the thingamajig. There we go.

Andrew Hutchison: Wow, you’re really helping the story.

Kim Ryrie: What am I tip?

Andrew Hutchison: You don’t want to do room correction. That’s the word I was after. You don’t want to go active. If you just want to tweak the speaker a bit.

Kim Ryrie: Not even tweak.

Andrew Hutchison: You just want to use it as a music play.

Kim Ryrie: Nice pair of speakers at home. very nice.

Andrew Hutchison: Plug in your old CD player, which it will do. Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: But you’ve got a pack.

Andrew Hutchison: You can Bluetooth your partner’s phone.

Kim Ryrie: You could buy that today, couldn’t we?

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, and it works perfectly. So that’s.

Kim Ryrie: That’s what I like.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, the one downstairs that we saw working did appear to work perfectly.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah, exactly. So the point being rolling start. In all seriousness, you could just buy one today and have that. But the bonus, it’s not the steak knives and all that. So the use of things, you will get a microphone with that and you do. Will have the ability to do room correction and all the other grows. Yes.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah, yeah, that.

Kim Ryrie: That’s the, that’s right.

Kim Ryrie: The. The challenge for the whole Gen4 platform was to be able to compete with the highest end DACs that are out there.

Kim Ryrie: Right.

Kim Ryrie: You know and, and just have the analog transparency top of the line. So that

01:00:00

Kim Ryrie: effectively price wise the deck stuff should essentially be free. You know if you were to go buy high end streamer DEQX preamp, thing. Same sort of price. Yeah as the, as the recommended retail but for now.

Andrew Hutchison: Serhan Swift Bespoke loudspeakers Designed and built in Australia by perfectionists described by reviewers as exceptional. Serhan Swift has received numerous awards here and abroad including sound and image best stand amount loudspeaker 2024 for full information head to Serhanswift.com yeah basically half.

Kim Ryrie: Exactly retail price because it’s.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah it’s a hell of a deal. And what you say is probably the most important point and that is the quality of the stuff that you’re really listening to. The quality of the DEQXs, the way the volume control circuitry works, the normal preamp stuff and then the quality of the streaming and the phono is all and phono stage. The point is. Yeah particularly the price you’re selling it for at the moment. That is it’s a great value for money Preamp the deck stuff is for free but it’s always for free anyhow because even at the price you’d like to sell through normal channels, it’s To me it sounds, I mean you say it seems expensive, I say no.

Kim Ryrie: 27 years worth of development as well.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, I think it’s very good value for me.

All our pricing is in US dollars because that’s our biggest market

Kim Ryrie: And may I ask what that prices? We probably mentioned it before for that, you know.

Kim Ryrie: Well all our, all our pricing is in is in US dollars because that’s been our traditionally our biggest market. but About 80, about 95% of everything we’ve made traditionally is export. Right. Europe’s picked up a lot lately but so, but we still advertise in US dollars. So the list price of say a pre 8 at the moment is 15,900 US. That’s list MSRP. our beta price actually we’ve only just announced that you can have not all the options for the hardware. You don’t have to buy the Dyna Vector. no Rodeo. Okay, you don’t have to buy. You can add them later though. you don’t have to buy say the XMOS USB input. You don’t have to buy the digital outs which gets the beta price below 6000 US it’s, it’s 5950 I think it is.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And then it ends up at about 6950 if you have all the extras.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: So it’s a lot down from the retail price but that’s normal wholesale. See that’s the way the industry works. The reason this high end audio stuff is expensive is because the dealers need a lot of money. The importers get so much percent the retailer.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, they’re all doing something, aren’t they. The distributor has to warehouse it and.

Kim Ryrie: Market it until promote.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah. And then the retailer has to spend a lot of time educating, educating, talking to people and learning about how to use, use it and, and of course putting it all on display and in a bricks and mortar costs money building.

Kim Ryrie: So I might add the pre4 are a bit cheaper than that and so is the LS200 of course.

Andrew Hutchison: Right. Sounds to me like though if you do buy it direct from you at the moment that you get really high quality levels of service, you’ve got this team’s arrangement, you’ve got, you’ve got a team of people here to help support the product. It’s not like you’re left on your own to try to work out how it might work. It’s. There’s a huge amount of support.

Kim Ryrie: So I think when, well we, for the beta, we do directly. Yeah. for the beta members, when dealers start handling their profile. Yeah. We start charging.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah. As you.

Kim Ryrie: For direct support. But the dealers would typically do that.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, but my, but for the beta program you’re getting a high level of backup service, you’re getting new guys direct.

Kim Ryrie: And you get the normal warranties and all that sort of stuff.

Kim Ryrie: You’ve got the DEQXperts and you’ve got the ability for the DEQXperts to go in virtually.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes. And help.

All right, well look, look, thanks again Kim for,

All right, well look, look, thanks again Kim for, thank you many hours of your time. Really appreciate it. The tour of the factory, we’ve got a little, we’ve got enough video footage. We’ll have a little video up to show people, what’s going on downstairs. It’s pretty impressive. thanks Brad. Thanks for your input. Lots, of interesting questions. couldn’t have done it without you. thank you so, a pleasure.

Kim Ryrie: So thank, you Kim.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes, thanks again. And look, anyone who’s got any questions, get in touch with Kim. the details will be on our website and not an audio file. Thanks everybody and we’ll be back soon.

Kim Ryrie: Thank you.

Kim Ryrie: Thanks guys.

Andrew Hutchison: Pleasure.

Andrew Hutchison: If you’ve enjoyed the show and you must have because you made

01:05:00

Andrew Hutchison: it this far, can you please perhaps give us a five star, review if that’s.

Andrew Hutchison: What they call it on the platform.

Andrew Hutchison: That, that you prefer. So thanks again for listening. See you in the next episode.

01:05:10S2 EP023 – 1 simple step to speaker and room sound correction with DEQX and designer, Kim Ryrie.

Glenn Dickens virtually co invented Atmos at Dolby

Kim Ryrie: We’ve got Glenn Dickens. Now Glenn was running R and D at Dolby for 15 years.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: he virtually co invented Atmos at Dolby. He’s now working for us as we speak. He’s in the room next door on the blower with Joe, trying to sort out a time alignment issue in, in the, the Bass integration algorithm.

Episode 23, season two of Audiophile features Kim Ryrie on DEQX

Andrew Hutchison: And welcome back to not an Audiophile.

Andrew Hutchison: This is episode 23, season two. Today we speak to Kim Ryrie in part two.

Andrew Hutchison: I said it would be a week, it’s been weeks. I apologize for that. But we’re now back.

Andrew Hutchison: Brad and myself, speak to Kim , make little titters and comments and probably talk over each other a bit too much. We were highly enthusiastic.

Andrew Hutchison: We just seen downstairs where the

Andrew Hutchison: DEQX product was manufactured.

Andrew Hutchison: We met a number of the

Andrew Hutchison: Incredible people that are involved and frankly we were a little awestruck. Kim today in part two tells us.

Andrew Hutchison: Really how DEQX got a start, what.

Andrew Hutchison: It really is, what it does, and how Gen4 is a significant improvement in refinement over the previous generations.

Meet Spectraflora, Australia’s newest loudspeaker innovator

This episode of not an Audiophile. The podcast is sponsored by Spectraflora. Looking for gorgeous speakers that sound as good as they look. Meet Spectraflora, Australia’s newest loudspeaker innovator. Their flagship Celata 88 is handcrafted in Victoria, Australia. With patent pending waveguide and subwoofer designs, this speaker delivers impactful, dynamic and emotionally gripping sound. Listeners rave about the beauty and breathtaking.

Andrew Hutchison: Sound of the Celata 88 at makes ordinary speakers feel lifeless.

Andrew Hutchison: Experience Spectraflora rediscover meaning in music. Learn more@spectraflora.com great to have you back.

Andrew Hutchison: In the room, Kim. it’s been matter of minutes since we finished episode one and now we’re recording episode two. But we’re going to strike while I, Brad Serhan’s here as well to help us. the deck story started a lot longer ago than people realize and as you’ve joked, the the oldest startup in the history of startups. I mean 96, I think you just.

Kim Ryrie: 97.

Andrew Hutchison: 97, yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Look, the triggered I should say.

Andrew Hutchison: By your, from the previous episode, your amazement, perhaps at how well analog active loudspeakers worked.

Kim Ryrie: That’s right.

Andrew Hutchison: And so no doubt there’s a connection between that experience with the Arty Jack band.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So, so just.

Andrew Hutchison: And why you started DEQX. Yes.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So just to recap on that story, we had a band back in the would have been early 70s and and we had a pair of Altec A7 voice of the theatre speakers using the passive crossovers that come with those. And we were blowing the horns up almost every month or two we’d blow the diaphragms up on the horn. and at the time I had a couple of hundred watt amp modules and someone suggested taking them active, which meant having one amp for the horn and another amp for the 15 inch woofer. And then I just built a four pole, 20, four decibels, per octave crossover in front of each amp. And what amazed us was just how clean suddenly the voice of the theatres became. And because of the steeper crossovers we stopped blowing up the horn.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: So that was my first realization of the advantages of active, especially for clarity, you know, minute, you know, reducing crossover distortion in particular. because you know the, for example with a passive crossover you’ve got a 15 inch woofer, that woofer, ah, if it’s got a slow roll off above the crossover frequency. I think the crossover to the horn was about 700 hertz or something like that. you know that’s still outputting nasty stuff up into, not up into 1400 hertz and higher because it’s only rolling off quite slowly. Meanwhile the horn is upset because we’re sending a lot of bass frequency to it which it doesn’t like.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: So it’s, it’s nearly at its, you know, X max and getting distorted apparently.

Andrew Hutchison: Beyond its X max and beyond judging.

Kim Ryrie: By your, in our case beyond it.

Andrew Hutchison: Diaphragms a dozen at a time.

Kim Ryrie: Flying diaphragms.

Kim Ryrie: that’s the name for a band.

00:05:00

Kim Ryrie: So anyway, so long story short, yes it is.

Andrew Hutchison: We’re talking horn diaphragm.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. So, so long story short.

Andrew Hutchison: But I, but I didn’t, but it planted a seed.

Kim Ryrie: Obviously I wasn’t involved in speakers after that because the Fairlight distraction went on for 20 years or something.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And then But in, in Fairlight I’d started using a lot of D. Another good name.

Andrew Hutchison: For a band, the Fairlight Distraction.

Kim Ryrie: But anyhow, so so you asked about how we started DEQX, which the original name was Clarity eq.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: And what had happened there was one of our programmers, guy called Brian Connolly had left and started his own company called Lake DSP and Lake, had that name.

Andrew Hutchison: Rings a bell.

Kim Ryrie: Yeah. Lake had come up with this headphone technology whereby they come up with some HRTFs, which is head related transfer functions, which is sort of how the ears work to Determine where sounds are coming from.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: So each ear filters in a certain way. And if you can reproduce the way the ear is filtering by actually sticking a microphone inside the ear.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: Creating, you know, doing a frequency sweep, impulse sweep, I should say. you can create, ah, a filter called an FIR filter. Finite impulse.

Andrew Hutchison: Yep.

Kim Ryrie: Response filter. And you can mimic, if you just stick headphones in your head, you can mimic the sounds coming from outside of your head rather than in between the headphones. And this was this technique that Lake had working and they contacted me. I was working at Fairlight at the time and I was sort of winding down a bit at Fairlight because by then we had venture capitalists and we had lots of politics and I was getting a bit sick of it. And I bet Brian said, can you help us commercialize this, this stuff because we run out of money and need to get investment. Yeah. And so I went and heard it and I said, well, the first thing you got to do is make a little demo. So I wrote a little script with, with Q, calling James Bond into his study to point out that the Russians were trying to get hold of this technology which make headphones work outside of your head. And good Lord, Kyu, this is unbelievable. And of course you put the headphones on and you can hear this happen.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kim Ryrie: And we ran into, we made this little one minute demo of this and it landed on Paul Keating’s desk, who was the ex prime minister. And and Brian had met Paul out in the street and they had a chat, met him in the street and yeah, because that office was next door in the city. And and Brian was explaining, he got. Paul politely said, oh, what do you do? And he said, oh, we make this technology. Oh, that sounds interesting. And Brian says, would you like to hear it? So anyway, we, we sent up a little CD battery. CD player with headphones. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kim Ryrie: Landed on Paul’s desk. And next day he was in Lake’s office saying, this is unbelievable. Hooly Dooley. This is fantastic. Hooley Dooley. And show us around. And so long story short, Paul introduced Lake to a rich friend of his who invested a million bucks or 2 million or something. Lake ended up going public. but meanwhile, I’d helped him do all this and, and I said, Brian, do you realize you could use this FIR filtering, technology for loudspeaker correction?

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kim Ryrie: You know, you could measure a loudspeaker like we’re measuring the ear, the inside of the ear, the Inside of the ear was. All it was doing was just giving you an impulse response of what the ear was doing. Which amounts to the same thing as what a speaker’s doing the other way around.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, but in verse, effectively. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

FIR filters can correct frequency response, but they also introduce timing errors