Not An Audiophile – The Podcast featuring episodes with Kostas Metaxas from Metaxas & Sins. Why should HiFi be mundane, when imagination, creativity and an aura of playfulness can create visual as well as musical pleasure.

Podcast transcripts below – Episode 033

TRANSCRIPT

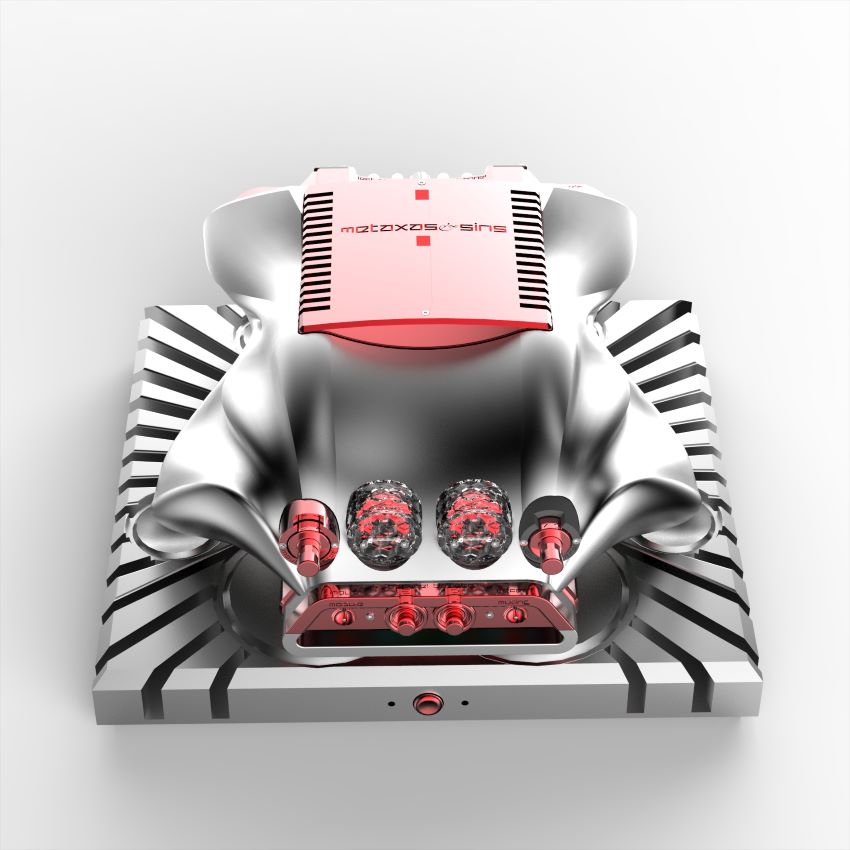

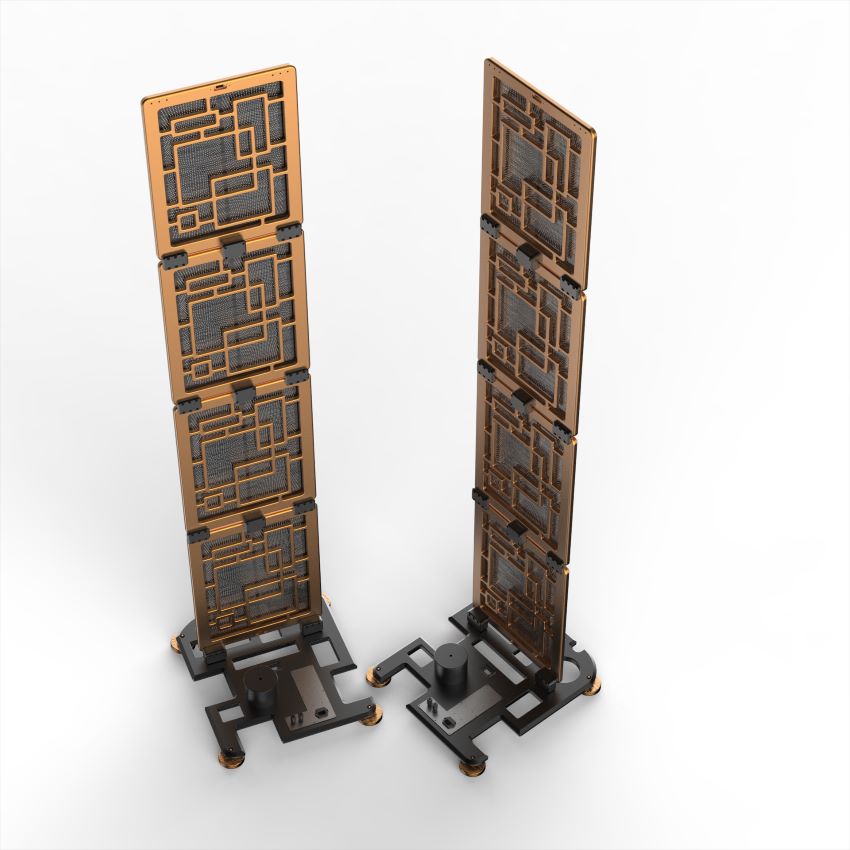

S2 EP033 Where sound & art collide. Sculptural, futuristic, fanciful and musical. Metaxas & Sins

Len Wallis Audio has been guiding HiFi enthusiasts on their audio journey

Kostas Metaxas: In the future, if you go in 20 or 30 or 50 years from now, you will see my objects coming up in Sotheby’s or Christie’s.

Andrew Hutchison: And hello, welcome back to not an audiophile episode 33, season two. And today, finally, a break from loudspeaker designers. As we speak to Kostas Metaxas, who not just designs loudspeakers, but everything. Turntables, open reel machines, amplifiers and speakers. We find out how the hell he made an open reel tape machine from thin air.

Are you craving incredible sound? I think we all are. Well, those listening to this podcast. For over 47 years, Len Wallis Audio has been guiding HiFi enthusiasts on their audio journey. They’re not some corporate machine, just a tight knit crew of audiophiles and entertainment lovers obsessed with great sound. From precision turntables to immersive home theatre systems, they hand pick gear that delivers. Stop by the store in Lane Cove, Sydney, Australia, or visit lenwallisaudio.com Len Wallis Audio, where your passion finds its sound.

HiFi RANT UNFILTERED

And welcome back to what my assistant suggests should be called the HiFi rant. Unfiltered. it’s not really a rant, but I do wonder in the future, as a lifelong audio equipment technician, who’s been fixing equipment forever, other than doing the other things that I’ve done, but that’s what I’ve done the rest of the time and gotten reasonably good at it with practice, 43 years worth of practice. Yes, I’m old, is that who’s going to do it in the future? Because in the last five years, in this country at least, I would say 15 quite good audio technicians have retired. That only leaves about another 15 to go spread thinly throughout 26 million people and a hell of a lot of real estate, I believe the rest of the world is in the same situation. So we’ve tried to employ people, both older technicians, who were qualified and maybe a bit rusty, but you know, that’s what they’d done at some point in their life and in most cases, quite recently. And we also spoke to some younger people and we spoke to them because they came to us and said, oh, I’d love to fix audio equipment, you know, and they may have specifically mentioned vintage because that’s, you know, kind of a favourite, of the 20 something age group that these guys were in. Now, I spoke to all of these four people. In fact, I put the two older of guys on trial and it just didn’t work out for a whole bunch of reasons, but bad habits not enough attention to detail, not really enough technical skill. in fact just, you know, not really that good for a qualified tech. So I spent some weeks trying to train them and they didn’t take that very well. They thought they knew it all and so they both, Well, one was asked to leave and one left largely of his own accord. The young guys though were interesting or more interesting because they were really keen on being, you know, an audio tech. Now that tells me that they thought there was a living in it, which there is. There’s a living in fixing audio gear now, perhaps like there has never been. you, you can charge a decent amount of money the same as probably any other, you know, like an electrician or a plumber or someone who can charge their time out because they’re. This service is important and it is important to fix audio gear now because there’s a hell of a lot of it out there. really there’s as much gear as there’s ever been, plus whatever’s been sold new on top of that, which at some point, you know, is going to fail in some way or another. There’s so much work and as, as the work piles up, which it literally is at our workshop, there’s less and less people to do it. So the rant, which is not a rant is can someone please, who’s interested in wanting to become a technician at your local area, follow up the workshops that you can find and talk to them about how you might go about getting trained. There is, as I understand it, no qualification as such worldwide. There certainly, isn’t in Australia, I’d say the youngest good technicians, the lifelong technicians that have a broad range of Skill are around 55 or older. So in less than 10 years there will be no one unless we train some people up on with the show.

NEWS

And another new but brief segment we’ll be having in the future and on a continuing basis is some news. And in HiFi News, PS Audio have released a new signature range known as the PMGs. it’s just out. It’s very exciting, they tell me. And it looks, I have to admit, it looks amazing. I have not heard it yet. I will be soon. the news leaked to me via, in fact, probably one of the only dealers in the country with any in stock. Jeff at Hey now HiFi has the preamplifier in stock now, so I would make an appointment and go and have a listen, give him a call. He’s his number and details, et cetera.Are on heynowHiFi .com au

KOSTAS METAXAS – METAXAS & SINS

we’re, we’re on the phone with, Kostas Metaxas today at. Not an audiophile . Thank you, Kostas, for answering the phone in Greece. As you were saying. So you’ve. How long have you. How long have you been living in Greece for?

Kostas Metaxas: Well, basically, on and off for 20 years.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And then, spending more time here over the last, say maybe 10 of those years or 12 of those years. But, I’ve also been spending time in Amsterdam where I’ve got my company based. And, before that I was in Berlin, and, obviously before that I was even working, out of London and New York. So I, Basically not too sure if you know my story, but I was born and bred in Melbourne, so I’m 100% Australian.

Andrew Hutchison: I was going to say before. Before you were in, Berlin and London and what have you. Of course you were in Melbourne. so. So, yeah. So born in Melbourne.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, yeah, born in Melbourne, educated in Melbourne, went to Melbourne Uni, obviously high school, all that sort of stuff. So, you know, I’m dinky die Aussie. and then, you know, I was going overseas to Germany to do some studying, because I was interested in medical technology. So that was where it all started.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And, when I went overseas as a hobbyist, from the age of about 13, I used to build my own kit, because obviously I couldn’t afford to buy stuff. So, you know, I was a kid. And, And so when I went to Germany to do my studies, I sort of did two years in Melbourne Uni. Then I transferred, after the second year, in the third year to, a, university in Germany. And, whilst I was there, I met some, similar minded people who love music and HiFi and all that sort of stuff. And one of the chaps introduced me to his father, who was a really crazy, very, very wealthy, jazz pianist actually based in Mannheim. And he had a very extensive setup. And again, I’m only a student. I was only about 19, years old or, you know, so, you know, I was quite amused by all this and of course all the brands that I used to dream about in Australia, because, you know, you didn’t get the variety of brands in Australia or Melbourne, Australia that you got if you were living in America or in Germany, for example, in those days. And so, he sort of said, I’ll introduce you to my dealer in Mannheim who was a HiFi dealer who had all the Most expensive stuff. And, they were obviously a bit amused with this little Aussie kid with his little amplifier. I took with me a little preamplifier that I built because obviously I wanted to have something to listen to when I was there.

Andrew Hutchison: Sure.

Kostas Metaxas: And as a student. And, so they took me to this big shop. And, in that shop they had all the top brands at the time, which were Levinson, McIntosh, you know, accufase, all these from Japan, from England, from. From wherever.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: And, he put a. Put on a system and it sounded pretty nice, you know, it sounded okay. Nothing spectacular. and of course, I never, ever heard prior to that a really big serious system. Because again, even in Melbourne in those days, you could never hear anything like that. It was just not possible. Alex Ensel was probably the only guy who had some esoteric stuff, but even Alex didn’t have the super esoteric stuff. and, so basically it came to the point where they said, look, let’s. Let’s hear your little preamplifier. And I said, yeah, sure. You know, I was interested to hear what the comparison was. Now I have to explain that, as a kid from about the age of 13, 14, I was using quad electrostatics, the 57s, which, were quite, you know, serious speakers. And in fact, they were instrumental in making me realize that you could actually have a realistic facsimile of a recording in space, you know, in your hi fi. To listen to with hi fi. And if it wasn’t for the quads, I would never have known that that was possible because with normal box speak and all that stuff, you could never hear, that sense of realism. But anyway, so that’s how when I designed my stuff, I was designing it with quad ESL 57s. And, so when my preamp was plugged in, and of course they’re all waiting to hear it to sort of try and explain to me then, you know, what I’m doing wrong and what I should do. You could almost, see them getting ready to, you know, help me evolve as a young audiophile. That sort of stuff. And then the irony was that when they turned, put it on, played the first piece of music, basically the preamp that I bought with me to Germany, this little tiny thing was a lot better than the stuff that they had at the time. And,

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And I thought. Actually, I was quite shocked. I thought, no, that’s not possible. I mean,

how can a kid from East Kilo in Melbourne, build something better than all these super brands, you know, from America, from Japan, from Germany, etc. And so as soon as they heard it, instead of, you know, they were about to tell me what I should do and how I should do it, blah, blah, blah. And that turned around very quickly to how can we buy this and how many can you make? And I said, okay. So at that point I had to make a pretty quick life’s decision as to whether or not I was going to do, you know, medical technology, which in those days was in its infancy, particularly in Germany, or hi fi, which was my passion, which, you know, as a kid I was always, totally nutter, you know, for. So of course I chose the latter. And then of course came back to Australia to my parents disappointment because of course they would rather introduce me to the doctor in the family than as the the electronics wanker or whatever they thought I was. Well, see, the thing is, I have to tell you, my, my mother, once, you know, because I got back to Australia, started producing the stuff Germans. And so my first market was Germany. And my mother in those days, my auntie would ring up and say to my mother, or ask my mother, send over Kostas because my toaster is not working. You know, so. Because I was. And I had to explain to my mother, no, I don’t fix toasters, Mum. I’m you know, I don’t do that.

Andrew Hutchison your early amplifiers were quite unusual. And interestingly, I guess the quality remains today

It’s nothing to do with what I do. And they were obviously, well, what good are you if you can’t fix toasters? So because again you got to remember we’re talking in those days, high end audio was quite serious amongst a group of individuals. But it wasn’t mainstream. Mainstream was cut and all that sort of stuff. So basically that’s how it all started. And how I ended up, all over the world was purely because for the audio business, ironically, the audio business then took me to all these places because once I started getting reviews in Germany, then other countries took note. Ah. And so, you know, my biggest markets in those days was Germany, Switzerland, Holland, you know, Denmark, all those places, because they were reading the magazine called Das ohr which was the equivalent to the absolute sound in, in America.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And Klaus, Klaus Renner loved what I did. And the only other person he mentioned in the first review he did of my pre preamplifier was Trevor Lees. Because he was saying that the only other Australian that he knew was Trevor, of course, because Trevor at the Time had gone to the States and, he was doing some work in California and that he. That he was from Australia. So that was the only. The only two references to anyone from Australia ever doing something in hi Fi. And look, the irony was that, that sort of started something. And of course, for me, I never imagined that my stuff would be that good. But it just made me realize it wasn’t that I was that good, it was just that the other stuff wasn’t that great. So in other words, it wasn’t, How can I put it? It was a ironic moment that, as a young man, of course, as a, you know, a young adult, that I realized that I could do something, you know, like, you know, at that level. So m. And that’s what defines everything I’ve done since it’s.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, that’s fantastic, insight. Thank you, Kostas, for how you got a start. And interestingly, I guess the quality of the casework of the preamp, that you turned up with was probably not as Fancy as the McIntosh, Levinson, whatever else was in the store that you were listening to prior to plugging yours in. But of course in turn now really your casework, your overall designs, if people are not familiar, I mean, Metaxas is the most organic looking HiFi product on the planet, obviously, with. With almost out exception, I would say. And Well, I mean, but. But your earlier, earlier works were, Were more rectangular, but they were still quite unusual. And my, knowledge of your existence, goes back to, I think about the start of the 90s, maybe 1990 itself. A customer wanders in with a magazine with a picture of one of your amplifiers and says, I want to buy that. And, then you sold it to me and I sold to him, and then I sold a few more. And it’s the thing that I can say is that they really did sound terrific. you know, they were a very open, fast sounding amplifier. And reading some of your information on your website, it seems that a lot of those ideas that you had in the earlier days regarding, amplifiers at least still carry on today inside the, the more mature and beautifully CNC machine casework of your current models. Is that the case or. Because certainly, certainly there’s no class D modules inside of them that.

Kostas Metaxas: No, no, no. I think, the most important thing that you learn in this business is if you, if something works, you have to keep refining it. In other words, basically from the day that you heard the amplifiers in the 90s, which is 30 odd years, almost 40 years ago. Basically today’s versions are just much more refined meaning much better quality components, much better matching, much ah, better isolation between the cases and the boards and understanding them mechanically and how that impacts sound. also the fact that the modules, the actual modules with the heart of the amplifier can be easily removed and updated enabled me to quite easily play with that. So you’re forever and even today you’re forever changing, playing with parts, wires, layouts, PCB layouts, PCB materials. So in other words since those days it’s been mostly, obviously of course there’s been some major improvements, but that’s been because of the fact that everything else has improved in the meantime. In other words, you know back in those days, the resistors you used were either German or Chinese ironically and the Chinese were actually manufactured with old German machines. And you know what I found out very quickly back in the day was, and this is maybe a little bit heretical is that the German, the new German resistors at the time, the base legs, the Rordesteins, sounded very brittle and harsh and all that sort of stuff. Whereas the Chinese who are knocking off the previous generation of the same stuff sounded much more musical and liquid and all that sort of stuff. So basically the most important thing that you’ve been honing is your ears and it’s to understand what is what you know when, when something is a lot better. How do you know that? And also back in those days you’ve got to remember there wasn’t ah, you know, a lot of great stuff to pick from. So you virtually had to roll your own, in other words. My first turntable was a pioneer, direct drive motor, you know, turning a 30 kilogram aluminium platter on a granite plinth. That was the first turntable that I had that was serious and I was only about 18 or 17 when I had that. And so you had to sort of do a lot of stuff yourself. And I was very fortunate that when I got the notoriety in Germany I was able then to talk to other manufacturers that were doing world class stuff and I was able to buy some of that stuff to play with. For example in those days I was also dealing with Goldmund. When I came back to Australia, they were just started out and he had a great review in America with one of his tables. And so I started importing that into Australia and that obviously helped me develop my business as well.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: but it gave me Another level to listen to and also like a reference standard to other stuff that was about available at the time. so I was fortunate enough to you know, understand that the most important thing was my ears. And to that event I ended up also buying from Stellar Box in Switzerland, two tape recorders because I felt that as good as the turntable was back in those days, my biggest bugbear was that you could never get the same sound twice from a turntable. They were always, you know, depending on the temperature of the room, you know, all these things, you know, how much.

Andrew Hutchison: Crud was on the stylus, etc.

Kostas Metaxas: Yes, you always had So from an absolute point of view I found it always a little bit difficult. Although of course you had to design phono stages, which I did. But I found the tape recorders far more stable and far more, a much bigger sound and much more delicate, much more, just much more organic sound yet again than the turntable. Because obviously, to make a disc that comes from tape and then they have to modify it, they have to compress it, they have to do all these things to it. So if you could imagine that tape itself without all those artifacts, you could hear things much more than you could otherwise. And that’s always been the secret, the secret sauce in. If you look at the best products out there, the designer ah, has to have some way of hearing what, how good his things are. Otherwise what’s, you know, he can’t, you can’t sort of design in a vacuum. So when I was doing the design work back then with the Goldman reference for example, I had one of the first production Goldman reference in Australia and in the world at the time. I had it even before Harry Pearson had it. And at the time the only other manufacturer that had a Goldman reference as a turntable was Jardi in France, who ended up becoming my distributor in France too in the end. Okay, so so ironically again if you have, if you can hear it, you can design with it.

The same with the quad speakers, the quad 57s which I also owned

The same with the quad speakers, the quad 57s which I also owned, you know, up until about the age of 23, 24, which I then you know, started playing with Martin Logan’s at the time because I was always an electrostatic nut. And then then I started

building my own because again I was lucky enough that the chap who was servicing and fixing the Martin Logan’s at the time, you know, I met him, we got on and you know, he basically explained to me the simplicity of it. And I thought, okay, let’s try some ourselves. And so that’s how it all started with the electrostatics. And of course now we also do electrostatics as well. But the truth of the matter is these things were always in my, in my mind, the top of the tree. And, but they were still crude. In other words, no one had perfected an electrostatic, up until those days. And of course Martin Logan was the latest flavor of the month at the time. But the truth of the matter is I don’t think anyone spent the effort on electrostatics, as they have on cone speakers. Because if you look at cone speakers, for example, the ones that you can get today are infinitely better than the cone speakers we had, you know, 30, 40 years ago. So, so basically that’s been always my mantra, which is you have to be able to hear so you know, if you’re going in the right direction. And then also when you hear a new product, when you’re developing a new product, you know, very quickly if it’s going to survive, if it’s going to, you know, have legs and be, something you can put into production or not. Because clearly not everything you create is perfect or it’s perfect because you want it. And so, you know, if it’s not, you just, you know, you. And I know you just. It won’t sell it just simply the customers will hear it. And they say that’s pretty ordinary.

Andrew Hutchison: It’s the customer is the. I mean you can bring whatever you like to the market, but if you, you know, play it, do a demo and it’s like, ho hum, then that’s kind of the end of that. I mean it’s, it’s, it’s a balancing act between all of the, the reliability, the appearance, the quality, the apparent quality and of course, probably most importantly, most of the time is the sound. but that brings us sideways to the other thing that is very important and that’s how it looks.

How do you come up with these designs, realistically

Although the other question I want to ask you is not just how you come up with these designs, but realistically, how do you do it all? Now I realize that you have dragged in what appears to be your, well, I was going to say sons, but I guess Metaxas and Sins is your sons. Is that, is that the gag? I mean just.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, of course now they help, they help me, but they’ve got their own careers as well, which parallel. In other words, my elder son, he’s an engineer, he does programming, he’s basically responsible for most of the tape recorders. So in terms of the programming and all that sort of stuff, because I can do the mechanicals and that’s all getting self taught. But the truth of the matter is, you know, if I don’t have help with things like programming and stuff, there’s no way I can go much further than just basic stuff.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: So, but, but if you want an answer to the aesthetics, the irony was when I was still a kid, you know, I was in my twenties, luckily I looked a bit older because I had a moustache. You know, the typical Greek moustache. You know, it makes even, even babies look bigger.

Andrew Hutchison: More older.

Kostas Metaxas: yeah, yeah. Look, I was lucky that when I was in my mid-20s, I was going to CES shows in, in Las Vegas. In those days that was where all the action was.

Andrew Hutchison: Indeed.

Kostas Metaxas: And at the Sahara. Hot. Ironically, what people don’t know or might not even know is back in the 80s, in the mid-80s and the late 80s, the Sahara Hotel had on the second floor a porn show, you know, pornographic video show. And on the first floor it had the high end audio show. I’m going to tell you that surely.

Andrew Hutchison: More, that’s more than a coincidence, surely.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, I’m sure. But basically in those days I’d have Nelson pass come into my room and have a coffee with me and Nelson was about, you know, 10, 15 years older, but he didn’t realize that he thought I was the same age as him.

Andrew Hutchison: Or you know, or they’re about.

Kostas Metaxas: But all of those guys, you know, Roland, you know, the guys from all the industries which I grew up in, because then that was also quite a treat. You know, again, you read about all these people and then you meet them at these CES shows and they’re also as intrigued about you, you know, because they’re saying who the. Excuse the vernacular, but who the fuck are you and where you come from? What planet did you come from? So, so it was, it was actually quite funny. But you know, ironically, back in those days, I’m talking now the mid-80s to late 80s, no, one in Australia really knew what I was doing. They, because I had a very low profile in Australia because I didn’t need to sell to Australia. I was selling, you know, my stuff overseas. And the only thing I started selling when I started selling Goldwood and stuff to Australia, in other words the local market, then they started getting to know that I was there. But they only saw me as a distributor, of these products and they you know, and you as you know, just hold on a second, I’ve got someone at the door.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, that’s not a problem. Yep, we’ll take a quick break and back in a second.

March Audio makes high quality amplifiers using purify components

March Audio, Fantastic amplifiers. Alan March has been on the show a couple of times. He’s a great guy, very, very smart cookie and he manufactures a range of amplifiers and loudspeakers using purify components in most cases which we all know are extremely high quality. So check out March Audio. Great sound, brilliant build quality and design. And in fact I believe there is a new preamp which is a ground up design of their own coming out from literally a clean sheet of paper. Marchaudio.com yeah, you weren’t, you weren’t well known except the distribution of a few super duper brands was obviously drawing some attention. And I’m going to say that 8990 must have been when you suddenly people maybe you brought out a few new models or something because I know you had models of amplifiers before that. I mean clearly you did, you were selling them in Europe. But I don’t, like you say, I don’t think maybe I was out of the loop. But I didn’t, as I say I didn’t know about the product until I think it’s the start of 1990 thereabouts.

Kostas Metaxas: So you know what it was Andrew? It was once I got some reviews in England, in the UK when I got the first review of course outside of Germany. And you know, it was obviously no one in those days. There was no Internet and no one bothered, you know, with what was going on in Europe. basically when Ken Kessler wrote up the Solitaire and the opulence and of course the soliloquies, that’s when, and that was light IDs and early 90s actually. Early 90s that’s when I got notoriety in Australia or a little bit of notoriety in Australia. because of course they were quite amused that they will have to pay, you know, ridiculous money in England for this stuff. And then they thought Jesus, so cheap here in Australia. But still, you know, it can’t be good because it’s Australian mentality. But then also I got some write ups in America in Stereo Review, which in those days a very big magazine in audiophile. Ah, with Bascom King who’s since passed away, who wrote up about the Solitaire and was, you know, was putting you know, one hundred fifty kilohertz into eight ohms and all this sort of stuff and Saying, my God, this thing, you know, is fast. So look, the irony is again, there’s no script you follow in life and things happen, you know, in strange and bizarre ways. But obviously it’s the universe probably telling you maybe this is your calling. but you know, in those days, that’s when I became a bit more known in Australia. But you know, Australia, you and I know, it just doesn’t take the local stuff seriously. I mean, the only other chap that was doing some interesting things in those days was me, was Peter Stein.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kostas Metaxas: and then of course you had a few guys from New Zealand like Perot. He was getting a little bit of traction in America as well. But, I think, you know, without sounding like a total wanker, I probably at least helped you know, get people to realize that you could do stuff in Australia. And of course since Australia has been a powerhouse of a lot of, you know, extremely, you know, well regarded products. So I don’t think, you know, that would have happened probably if there wasn’t another Australian doing, you know, crazy shit overseas.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, it all helps, doesn’t it? I mean, you know, the more the merrier. So, Exactly. So you were something of a pioneer, I would suggest. And you know, it’s. And then you’re a further pioneer because what you’re doing now and there’s people, people listening to the podcast who go, vaguely remember this guy. I’m thinking Australian audience, which is, you know, a percentage of our audience are Australians. majority is probably out of the country. But the point is that, I remember that guy. Is he still doing something? You know, because many years have passed and Yes, but, but of course, you’re doing amazing things. I mean the tape machine, I mean you, you’ve got all sorts, I mean you’ve got a full system, a complete system available from your product range, which I have no idea how you possibly design, let alone manufacture, but we’ll come back to that. But the, the tape machine, I get your history with the Stellavox and recording and using those recordings and, and other tapes you’ve made as a, as a reference for when, you know, listening to gear that you’ve been working on, amplifiers and the speakers. But at some point clearly the product, you

know, reel to reel tape recorders, open reel machines were not available anymore. And I guess you, you thought you would put a spin on the market in the sense that rather than relying on you know, rejuvenated older Machines, you’d create a new machine. Which seems out to me as someone who spent half a lifetime, or maybe actually a whole lifetime fixing the things. The complexity of a good open reel machine is and the precision of a good open reel machine is, you know, NASA space mission sort of quality. really, I mean it just has to be perfect. So how the hell did this start? Insanity? Because I mean, well, where did you start? I mean, did you start with the guts of something else? And then because you couldn’t buy all the bits, you changed it or what?

Kostas Metaxas: You can’t, you can’t. The look, the irony is the best machine I ever had and listened to and worked with, up until the point that I started doing my own stuff was, was still the portable Stellar box.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay?

Kostas Metaxas: Not the big one. All right, the big Stellar, despite having identical modules and stuff, it never sounded anywhere near as good as the small one.

Andrew Hutchison: What do you think that is? Just to cover that for a second?

Kostas Metaxas: Well, it’s probably a lot of things, but I think mostly to do with the transport. It has to do with the fact that even though George is. Look, George’s Keller is my mentor and he’s a genius and I love him to death. And he’s the most, underrated and under known because he basically created high end audio. People don’t know that, but Mark Levinson, who’s been attributed to, you know, inspiring, you know, this art mentality in high end audio, basically trained with Georges in Switzerland, you know, at one point of his life and when he was in a very important part of his life. And then he went back to Connecticut in the New York and started his company, which then of course inspired all of us, including myself. I know Mark personally. So you know, he, you know, I’ve talked to him about this many times, but he and I have a, you know, deep love and affection for Georges Kelly because he’s. Unfortunately no one really knows that this is the guy. This is the guy. But anyway, to, not to digress, his little machine. Yeah, with some, some simple modifications. Because you’ve got to remember, towards the later part of the tape world era, they started killing the machines with all this extra bullshit that it didn’t need, you know, limiting and this and this, which the machines of the 60s and the 50s of course didn’t have. Which is of course why those recordings of the 50s and the 60s were always infinitely better than the 70s and the 80s because by then they started using cheap op amps and started doing all that crap to the poor machines.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay?

Kostas Metaxas: So that’s why. And that’s the other high. So basically, the best tape recorders made before, you know, the stuff that I’m doing nowadays, were done in the 60s. You know, to be bluntly honest, the older studies were fantastic. The new ones, the transports, are okay, but the, you know, I mean, very precise, all that sort of stuff. but the electronic, ghastly. You have to basically gut them and replace them. And that’s even what Mark Levinson did with the, these, the old A80s. He used to basically gut them and put John Curls circuits in there.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay?

A tape recorder is basically a simple line stage with very small equalization

Kostas Metaxas: But what people don’t know is that a tape recorder basically is more or less. The, record side is a very simple line stage. It’s not very complicated with very small equalization because the record is very low inductance.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: And the playback is very similar to an RIAA moving coil cartridge stage. So in other words, they’re not complicated. It’s not magic. It’s nothing all that special. It’s actually very basic and very simple. And what makes a tape recorder even better than a, turntable is that it only really needs one time constant rather than three, which is what, you know, the RIAA has three time constants in an equalization curve, whereas ccir, which is the tape standard, only has one time constant. That’s it. So basically it’s a much, much simpler circuit, which therefore also helps in the sound quality. Now, the way I started was, of course, I was using the stellar box, the small stellar box as my starting point. And at the start I had the great idea because I didn’t know my ass from my head when it came to tape. Nobody knows. And the only other person that I knew at the time that, you know, had a little bit of extra knowledge was a guy called Jean Claude Schlup. Used to work for Niagara.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And, John Claude, he wasn’t interested to tell me, you know, how to make tape recorders. That’s for sure. Because it’s, you know, firstly, you rang.

Andrew Hutchison: Him up and asked.

Kostas Metaxas: Well, I got to know him through a friend of his, right? So. And we talked. Yeah. But, you know, he was a typical arrogant Swiss engineer, which, you know, they all are. And, you know, here’s this Australian, this Aussie guy, asking him about making a tape recorder. And it’s like laughing, you know, just. You must be kidding. What, are you on drugs? Are you drunk? So that was basically the normal reaction, in those days. And also so you couldn’t find Anyone to help you. So my first idea was to go to Jean Pierre Gudner who was the guy who was still running like you know, he used to work for stellavox and he was on the side servicing them. And he was also helping me update my Stellar Lock machines because I bought quite a few of them and had them modified to the SM8 standard, which is the higher biasing, current at 128kg rather than 64, which is the standard machine. and so my first idea, because he had quite a bit, a few, quite an inventory of parts was to make a small Stellar Box. But like with the ABR, which was the reel adapter that enabled to use 10 inch reels as a machine. So that was the first idea and I talked to him about that and then so that was where it all started. And of course what he then did was went off and decided to drop dead. So that was the end of that idea. So I mean I’m being of course psychiatrist. Yeah, exactly. So he, he sort of passed away. So I, that was the end of that idea and I spent quite a bit of time and quite a bit of money trying to do that.

Andrew Hutchison: So this was, this is the gentleman that was continuing on Stellar Box tradition who had the parts.

Kostas Metaxas: Yes, yep, yep, exactly, exactly. So, and also one other aside, just so then you guys know when Stellar Box went, went under because all the tape recorded companies including Studa, as you know, went bankrupt. They all went under. And the only one that didn’t go under was Nagra. And Nagra, what people don’t realize was the reason it didn’t go under wasn’t because they were such clever business people was that his son was a billionaire from the set top television business. So in other words, the son had a ton of money so he kept the business going. He thought what the heck, this is like a tiny little division. Right? And that’s the only reason why Nagra still exists today. And of course they don’t make tape recorders anymore. But the joke is, and now the sister runs it. But where I’m coming to was that when Stellar Box went under, sadly I made the fatal mistake because I was a Goldman distributor at the time to introduce Stellavox, to Goldman, to Michel Rebachon. and what people don’t realize is that at that time, of course when they went under, Goldman picked it up for nothing. So in other words, they were there at the right time. They swooped in, picked up. Yes, it’s the usual, you know, when something’s drowning, you know, you send them a line and pull them up and So he picked it all up for nothing and then of course did nothing with it. Which is also another bit of a travesty as well, sadly, because I was hoping he might at least try and do something. In those days he was in Paris, but then he went to Switzerland and I was hoping he might rejuvenate something and at least I wouldn’t have to bother to make something. But, that never happens.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, yeah, I mean, I mean, was your goal if you had picked it up at auction or however it was sold, you would have had tooling and drawings and parts. Is that the, is that, I mean, would that have given you a massive head start or did they not really have much left, really?

Kostas Metaxas: No, actually the irony is. No, it would have been a, it would have actually been a, big mistake. Because the technology to make a tape recorder today is totally different to back then. And what I’m trying to say is, back then, if you wanted to make tape recorders, firstly you had to get special motors made for you. And the motors that were available were, you know, the basic dc, you know, brushed motors. There was nothing really different to that unless you would like Stellar Box and make your own motors from scratch. So, that was the first problem. So therefore all your motor control circuits were based on a motor that wasn’t really designed for low torque, low speed. So ironically, when I started researching it, and this was also with the help of my son, thankfully, we started to realize that the only industry that was using the sort of motors we needed was the EV industry. Because there they needed something that can, have a high torque. Because obviously you get to move a mass of a car, from zero to whatever speed. You need something that has all that going for it. And also the controllers to run that, you know, Mosfets, you know, very efficient compared to say, the, you know, the more traditional oscillator way of driving it with power

transistors and amplifiers basically, that had all changed and you were able to buy off the shelf systems that you could play with, which obviously we did. And but of course, you know, they were never perfect because they weren’t designed for tape recorders. So. But at the same time, you know, all the turntable guys were using the same setup to do their, you know, to do belt drive turntables. So you knew that at least it was in the right ballpark, it was going to Be quiet and all that sort of stuff. So,

Andrew Hutchison: So you’re. You’re implying. You’re implying. Sorry, I just wanted to. So you’re implying that. So your tape machines are all direct drive. Basically. They’re so that. That kind of.

Andrew says it took two years to develop the Nagra T tape recorder

And by that, for those not so, okay, you’ve got three motors or they’re not auto reverse.

Kostas Metaxas: There’s actually six motors. You’ve got two separate real motors, obviously.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: And then you’ve got two cap stand motors. Because my machines are dual cap stand, but independently.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah. Okay. Still closed loop. Yeah. Okay. Yeah. So two, Two capstone motors.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, yeah, two cap stands, two reel. And then you got two. The tensioners, the linear motors to push the actual carriage up and forward to remove the tape off the head.

Andrew Hutchison: Of course. Yeah. Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: So the six motors. And basically what I was doing at the time when I was looking at it and researching it, I thought to myself, if I do something a little bit like. A little bit like a Nagra T and a Stellavox put together. And the reason I like the idea of the Nagra T was the fact that then you can control the speed sort of infinitely more than you can with just one pinch roller and one roller. So that was the reason that I went in that direction. And then also because then you could balance it better because then it’s basically a total closed loop. You don’t have the issue of something, one reel influencing it more than the other reel. So everything’s totally balanced anyway. So that’s. That was the idea. And then the irony was I had a guy, I met a guy who was able to do some of the other work for us. Because my son obviously wasn’t a motors expert and he was just. He finished university and so he sort of helped up to a point. But then we need to bring some other people in, which we did. We found a guy in Peru of all places, who was actually quite, quite clever. And we brought him here to Greece. At the time we were doing it in Greece. And at the time I sort of machined the guts of a tape recorder. And then he was there to make it, you know, make it basically work. And obviously that was the starting point. And then, he did that to the best of his knowledge, without knowing anything about tape recorders at all. Which was also good too, believe it or not. And Because sometimes if you know too much, because I had a friend at the time, for example, it was a fanatic for tape Recorders. And he kept telling me do this, to do this, to do this. And I said it doesn’t work. You know, this is because all the things he was offering, ideas he was offering were fantastic or stuff done in the 60s and the 50s that with the modern technology it just didn’t work. So you had to start with a clean sheet of paper. So this chap managed to get the basic system turning and then I realized how, you know, how bad my mechanics were because obviously then you could tell with the wound flutter being ridiculous and all this sort of stuff had to sort of then get that right. So basically it was all to and fro in. So luckily I had the electronics sorted so that wasn’t going to be the issue. But it still became the problem. When I say electronics, the audio, but the mechanic, the actual mechanical turning electronics were almost there. But then I had to get the mechanics to work because obviously they were letting it down. So it was a balancing act. And believe me there were times where I just thought no, this is too hard, seriously. And I was almost about to give up, you know, a few times because.

Andrew Hutchison: How many years are we talking about as far as tinkering? well, not tinkering, probably working virtually full time I guess to get this thing to work.

Kostas Metaxas: Two years basically. Two years, yeah. And also that’s pretty fast really.

Andrew Hutchison: I mean that’s.

Kostas Metaxas: Well yes, I had a choice. I had no choice, Andrew. The reality is if you don’t, you know, if it doesn’t work, you know, you can take 50 years, it’s not working. So the truth is, ah, either a certain point, luckily for me, at a certain point I managed to tweak what I had to do to get it to work again. Intuition, nothing to do with. You could read whatever you wanted to read about mechanics and this and this. But unfortunately it was only really through the work working with my Stellar Box machines. I had also bought Nagra machines of course, and Studer machine. I knew the machine. So I sort of had a rough idea of how they were working and the tinkering and all that sort of stuff. And so with all that I managed to get the first machine to work and make real music. And then of course that was a starting point and then I had to get it to make great music. Otherwise it’s pointless. You know, what’s the point of making a tape recorder with the sort of expense of. The motors I was using was with Max on motors used by NASA. Go through all that trouble for something that sounds inferior to a revox, you know. So, you’ve basically got to make it really sing. So the, The other funny realization at the time too, was that by actually doing the mechanics. And then also the electronics for the audio. At the same time, I was also able to make massive strides in both things. Because obviously I’d improved, my little stellar box, the electronics. But again, was within the limitations of the transport. So in other words, I couldn’t do anything to the transport. so I couldn’t then know how much better it could be. Until I actually started making my own transport, which is what I did. And of course, then it was to and fro and to and fro. Listen to that. How if I change the suspension, resonant frequency, what happens if I change the tensionometers? What happens if I make the tension stiffer or softer or all these sorts of things, you know, you have to, You know, all the springs, for example, that regulate the actual tension of the pinch roller onto the rollers, onto the actual capstans. All of this sort of stuff. You had to figure it out by just intuition and listening.

It can take a lifetime to refine a Given product really

A lot of listening. So. And luckily, I think that’s the biggest gift I was ever given from, a teenager. Was I could hear when something was going in the right direction. And then after that, I just kept pushing and pushing and pushing and refining and refining and refining. I’m doing that at the moment with my big electrostatics, which I’ve done. The first omnidirectional electrostatic speaker. And the irony is to, You know, when. You know, when. When something can tell you very easily that something’s changed, then, you know you’re in the right direction. Because then, you know, whatever you do, you’ll get instant feedback. And that’s, the critical thing of, When you’re developing and designing hi Fi. It’s like, I suppose, like making a wine, you know, when a winemaker.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes, let’s talk about wine.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah. Well, basically, I think what he. What he’s really doing is he’s, He’s. He’s got his history of his tasting notes. And his mentality of when the grapes were like this. Or when we picked them like this. So it’s all that. It’s just really experience that helps you, navigate. I think that times where.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, there’s. There’s a real value to that experience that, That I think many, discount perhaps. But, The reality is it can take a lifetime to refine a Given product really. I mean, I mean you really are. I mean, like you said with your amplifiers, you’re basically building on what you did in the 80s and refining that. And, and that’s how you get to something that’s exceptional. I don’t know how else you could do it. I’m pretty sure you can’t take a clean sheet of paper and get something astounding and perfect within 6 to 12 months. not something that. I mean, particularly amplifiers and particularly tape decks. I mean tape decks were a thing that were very. Well, I mean there was many of them made and they were. I look back at some of those things and go. And this is relation, in relation to your tape machine. I look at the older ones and go how they were. They were $1,000 or 2,000 or 3,000 or $4,000 in, in the, you know, the late 70s, early 80s, mid-80s, what have you, the heyday of good quality open reel? Well, you would say the opposite. You say the heyday is the 50 or the 60s. But bear in mind.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, exactly.

Andrew Hutchison: You know, you’re a couple of years older than me, so I’m more of a 70s, 80s guy. But anyhow, the point is that the mechanism quality is incredible. And that’s why when I say how do you make these things today at any kind of sensible cost? And I guess they’re not an inexpensive, piece of equipment, I guess, but the little bits and pieces, all the little doomly danglies and bits of mechanism, fine bearings and things. Is that. What, where do you, how do you go about getting all of that made? Is that something you just, just subcontracted out to some Swiss company or something or, or is it China?

Kostas Metaxas: Up to a point. Okay, up to a point. But if you go back in the 70s, late 70s, and you look at consumer decks like TX and all that sort of stuff, you’ll notice that they were pretty basic and they would use like one motor

and a lot of activators and rubber belts and all this sort of stuff to make it work. In other words, they weren’t anything like high end. And So basically, because that’s the only way they could do it to a price. The same with cassettes. If you look at a cassette, you know, there’s only one motor in it.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: All the other stuff is, you know, little levers and that which move and change and change, like a, you know, a pulley or something to make it do what it has to do. So they’re mostly mechanical and everything that’s done. Is done mechanically. where we’ve been able to make something a lot better is because there’s none of that. It’s all. Basically the motor turns.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah. Impressive.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, yeah, the motor turns and And basically the rest is on a very stable platform. And therefore you don’t get all this resonance. And, you know, imagine all these bits of metal, bits of flimsy tin and all that, you know, floating around, bouncing around to the music and then not influencing the sound. So.

Andrew Hutchison: No, indeed.

Kostas Metaxas: And then also you’ve got the situation with tape heads, for example. The heads used in Studas and and Nagras and stuff were always a lot better.

Andrew Hutchison: Where do you get a tape head where, You know. Yeah, I agree with the difference. I mean, obviously the tape head is really is. Is everything, isn’t it? Is, would you say, or.

Kostas Metaxas: No. No, it’s not. It’s not everything. A tape head is like, Basically like a pickup cartridge, like a moving coil cartridge. It’s the same mentality. You’ve got a coil and you’ve got some way,

Companies that make magnetic card heads are also making tape recorders

But it’s done magnetically by inductance rather than having movement in a stylus. So basically the companies that make these are the same companies that make the magnetic readers in an ATM for your bank. So anything that has a, you know, anything that has a card with a stripe that has, you know, that does all this sort of stuff. And there’s a company I’ve been using in Italy called Photobox, which makes, heads for all the banks and all the tolls and all that sort of stuff.

Andrew Hutchison: Right.

Kostas Metaxas: And they also make, you know, they’ve got the heads from back in the day when they were doing it. They obviously started off as a tape recorder.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh. So yes. So they. Yeah, so they were a components manufacturer in the 60s, 70s and 80s kind of thing for tape heads. Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: Yes. And then they made the first because, as you can imagine, they were using, readers and stuff in banks and all that sort of stuff. Or security. Security cards. When you scan a security card, you need some sort of head that reads the magnetic stripe. So basically they then obviously went off and did that. But they still kept the technology that they already developed in the old days for tape. So I was able to find them. There was another company called AM in Belgium, which is actually all made in Romania. There’s a factory in Romania that makes tape heads identical to the studers. They basically took the studer details. And of course, when the studer went bankrupt and it was out of patent, they started manufacturing them so you can get virtually knockoff. I mean they’re not cheap but because obviously nothing’s cheap now to make this sort of stuff. But reality is that you can get brand new studer heads now without a problem as long as you’re willing to pay €600 for them, which is a lot of money obviously. but the same with the photo box. The photo box are about the same. So you look at about a thousand dollars ahead, but then that’s not a lot of money for a good cartridge. So,

Andrew Hutchison: No, no, that’s right, yeah. Yep, yep.

Kostas Metaxas: And they’re new, they’re brand new. They’re not not, not a old thing that’s been cleaned up or relapsed and all this rubbish. and obviously because people are wanting to use it mostly for playback. Also a lot of the tape recorders I produce are just playback, only they’re not. Nobody bothers with record anymore. You don’t need it really.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay, that’s interesting.

Kostas Metaxas: Unless you’re a studio. Of course I’ve got customers who are studios as well. But the truth of the matter is I’d say a good, say 80% are to audiophiles who in all honesty don’t care about recording. They just want to play back some tapes that they’ve bought. And of course now the libraries of tapes are becoming much, much bigger and you can buy them, obviously they’re not cheap, but, but neither are you know, new pressed vinyl. So it’s not, it’s just the way we live now.

Andrew Hutchison: No, it’s absolutely true. I mean you can spend 2, 300, probably even euro on a, on a record or a double album or something with some special, you know, special vinyl, special weight, special effort made with the mastering or something.

Kostas Metaxas: I mean it’s, yeah, that’s the, the ballpark. Now for a decent vinyl, record is at least €200 or say about 350 Australian dollars for one of the special. Yeah, yeah, yeah, exactly. But I’m talking anything that’s been reissued. Not, you know, obviously, if you buy something that was from the 60s, you know, it’s different. But if you buy reissues which are remastered, all that sort of stuff, it’s, they’re not cheap. Nothing’s cheap. Unfortunately in the same with tapes, tapes are around the same sort of price. You’re looking at around €300 type, which is about 500 bucks or slightly less, for a decent 30 minute or 33 minute tape. So, but again, for the high end audio guy who has a pair of speakers that are $100,000 or $200,000, that’s not big money. So, at the end of the day, it’s horses for courses.

Andrew Hutchison: It is. And it’s, I’m sorry, my head’s just spinning because I’m starting to. While you were talking, I’m thinking about the. Just the amount of. The amount of moving parts in an open real machine. You’ve got to collect them all together and then you, you, you’ve got to. Someone’s got to sit there and screw it all together very carefully. Which you’re doing, I don’t know, in Greece at the moment or, or the, or the Netherlands or where.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, I’m sitting here in the workshop in Greece.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: I have a workshop in Greece and a showroom in Greece. The showroom is separate. Ah. And that’s a nice big space to be able to let people hear stuff. the workshop I’m sitting in at the moment, I’m putting together a tape deck for a client in Taiwan who actually records concerts.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And I’m just finishing it off for him so I can ship it. And, you know, bottom line is no to me. I suppose at my age, this is the perfect type of work. It’s like a watchmaker. You’re basically doing complicated work, but it’s, you know, at least at the end of the day, you don’t have to do tons of it. In other words, you know, I don’t produce, 30, 40 machines a year. So, you know, we use, if we’re lucky, maybe 15 machines a year.

Andrew Hutchison: Uh-huh.

Kostas Metaxas: And that’s it. That’s enough for me. I don’t. Look, the tape recorder business is not about making money. If people think that. I can’t imagine the money I’ve already spent developing these things. There’s no way I’m going to get my money back.

Andrew Hutchison: The R and D is always free. I mean, it’s got to be. The accounting will never work otherwise. it’s got to be developed for the love of it.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, yeah, exactly.

You’re one of two Australian manufacturers making high end audio machines

Otherwise you couldn’t do it. Also, imagine if I had, for example, I had a guy visit me in Munich a couple of months ago. Well, yeah, a couple of months ago now because it’s July. and, he used to work for Phillips in Vienna. and Philip. Vienna used to make tape decks as well.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: And he said to me, he goes, how do you do it? He goes, we had a team of 88zero engineers. And you’re doing it by yourself.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: With your kids. I said, yeah, well, I said, obviously it’s not, you know, we’re, you know, we’re not consumer, all that sort of stuff, so we don’t have to try and make it, you know, as cheap as type thing. And so he was just, he just couldn’t imagine it. But look, I think, to be honest, as I said, in retrospect, if I had to do it all over again, I would have told myself, no, don’t, you know, you’re gonna almost pull your hair out.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: but when you succeed, when you actually get it and. Right. And it works and you know, even now it’s better and better than it was even a few years ago. and then you get great reviews, of course, where people are starting, I mean, for example, in the absolute sound, which is I think still the bible for high end audio. The irony is they’ve called it the Absolute Sound. So I think they’ve never called anything the Absolute Sound before. So, the truth of the matter is to be an Aussie, to come from nowhere and make something that crazy and then to get that accolade, at least that’s between you and me. There’s your payment. That’s how you get paid at the end of the day.

Andrew Hutchison: Well, there is a bit of that, yeah. I mean, you’ve sort of, you’ve clambered and made your way to the top, basically. And, and so as I understand it, there’s. I don’t know how many manufacturers currently have open real machines on the planet, but I’m. I think you’re one of two. Is that, is that, is that what you know or. Because m. There’s a,

Kostas Metaxas: Well, I think, I think in terms of high end audio, we’re the only one, to be bluntly honest.

Andrew Hutchison: Yep.

Kostas Metaxas: The other chap that I know of, there’s a company in France,

it’s the one. But he’s. Yeah, he’s using belts for everything, which is to me a. No, no. In other words.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: you know, you might know with belts, after five or six years, they’re gonna fall off or they’re gonna start gluing up all that sort of stuff. That’s why I hate anything rubber in the tape recorder. And of course the only thing that we’re using that’s rubber is the capstan roller. That’s it. of course you can change that quite easily. So, he’s a lovely guy, very nice machine, but you know, done differently. He’s not a high end guy. And then there’s the other guy, Reevox bringing.

Andrew Hutchison: Revox bringing theirs back maybe.

Kostas Metaxas: I met the guys from Reebox, the guy who runs it, and basically he told me that Revox had a big warehouse in Germany with just all the parts from the old, Revlocks machines.

Andrew Hutchison: Is that right?

Kostas Metaxas: And so basically, yeah, they had, Because obviously when they used to make them in the day, they used to make, you know, things by the thousand, not BY Tens or 20.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, indeed.

Kostas Metaxas: So they had like stocks to do another thousand machines. Literally.

Andrew Hutchison: Oh. Oh, wow. Okay. Yeah, all right.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, another thousand. So in other words, the joke is. But you got to remember back then the Revox retail price was 2,000, you know, Deutsche mark, which is like a thousand dollars, Euros. All right, so which is like 2000 Australian dollars.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kostas Metaxas: Now of course, now of course, they’re selling them for 16 to $20,000. So it’s a, it’s a. But you know, obviously like everything, it’s a business. So. But they’re not going to sell the thousand. But at least they’ve got stock. So bottom line is it’s a business, obviously, and they’re taking advantage of it and good luck to them. You know, that’s the end of the nature of the business. If somebody wants to buy, go for it.

Andrew Hutchison: I mean, you effectively, bizarrely have a thousand machines sitting in the warehouse. Someone just needs, you know, obviously make some front panels or front panels or something.

Kostas Metaxas: they’ve got everything. They’ve got all the parts. All they’re missing is some basic, you know, maybe some new heads which they get done now by Also Photobox does it for them. And at the same time, the electronics, they just do new boards, you know, with, with the op amps rather than the old, you know, discreet stuff. Yeah, they just do totally new boards which cost nothing with SMD components, you know, surface mount and it’s easy peasy. But look, good luck to them. Obviously the market’s there now for it. So if they can 16 to $20,000, you know, that’s not a bad thing. It means obviously that people are taking tape deck seriously. But I know, a turntable now, you know, you can’t buy a turntable for peanuts. I mean, a decent turntable. Gone are the days where you could buy, you know, in America, for example, a Linson deck or a Sota 6, $700. You know, those days are gone. You know, you can, that’s the price Of a rigor now. So, it’s, you know, totally different world now that we live in. Yeah.

Andrew Hutchison: The value of money is something that strikes me as, something that it doesn’t actually have much of anymore.

At one stage there was no suppliers of any tape. Today there are two companies making tape

Hey, what do you do for tape? What do you, what do you like in a tape these days? What if you’re buying blank tape? Because you are. And obviously, for instance, your Taiwanese customer is going to be using tape. He’s making recordings or she’s making recordings. what, what do you like? Have you got a recommendation? How do you buy.

Kostas Metaxas: There’s a company called rtm, which used to be, One of the funny things, when I was doing my recordings back in the the 2000s, I did a lot of recording at BMW, Edge at Hamer, hall at Melbourne, Town hall at the Opera House, all that sort of stuff. And even at festivals, the irony was back then, because there was the. At one stage there was no suppliers of any tape. I used to have to buy seven, inch reels of, BASF 468 and stick them together, put them together to make a. So and I was able to buy that in America because you couldn’t find it. Here I went. The first thing I did when I started doing my serious recordings was I went to every studio in Australia and bought all their pancake. And the pancake they had at the time was the 468, which was still my favorite tape. And in fact, I’ve got over 100 rolls of pancake of 468. Ah, stored. Because unfortunately now, recording the masters, RTM, they don’t make it anymore. They stopped making it. that formulation, all they’re making now is their 900 formulation and their 911 formulation, which is fine. It’s not a problem. It’s pretty, pretty good as well.

Andrew Hutchison: Okay.

Kostas Metaxas: but the truth is there are, there are. There’s two companies making tape. One is called atr, in America, which is the old amp.

Andrew Hutchison: Sorry, the phone just cut out. Did you say that was the old. Is the old Ampex, did you say?

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah, yeah, old Ampex Factory. That’s, They still make for studios, of course, in the States and of course then you’ve got in Europe, in France you’ve got, rtm, which is, basically recording the masters, they call it. You can find it on the web. They sell tapes as well. So you can still get tapes. It’s not a problem. Ah. And you know, obviously there’s still enough demand that they still can produce it. But the problem is for RTM and all these companies is that to set up a machine to do a run, they need a minimum quantity of quite a few tapes as you can imagine. So and of course quarter inch tape basically is done by slitting a very, very wide, you know, piece of plastic.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: So so basically that’s their, their biggest problem is, you know, to turn on the machine and to make a run of tapes is not economical. So that’s why of course, tapes now are quite expensive compared to what they used to be.

Andrew Hutchison: An Australian loudspeaker legend has been born with a stunning new VAF Research i93 Mark V, winner of Stereonets Floor Standing Loudspeaker Product of the year and Sound and Image magazine’s Floor Standing speaker of the year, $20,000 to $50,000. VAF’s i93 has redefined what I thought was possible from a loudspeaker in a domestic setting, says Stereonet VAF research. Building award winning loudspeakers in Australia since 1978.

Kostas Metaxas is the man who makes everything

And we’re back, back with Kostas, Kostas Metaxas, the man who makes everything. And in fact, sounds ridiculous, but I mean you, I mean, lucky you’ve got your kids to help you. And of course you have this, this, I, I guess you’d call it a team of people that you’ve met over the years who, who have some secret knowledge who can assist you to make these contraptions work. I mean you design everything in as far as the exteriors, as far as the casework, in some kind of a 3D drawing package. I presume that you’ve become quite familiar. I mean I can’t imagine you, I mean surely that, that is the, the, the essence of your skill is your eye and your ability to, to draw. Is that because that is what you do, is it? Kostas, tell us all about that.

Kostas Metaxas: Well, okay, basically about maybe 23, 24 years ago I started looking into CAD systems because obviously to do printed circuit boards was pretty basic. There’s a company called Protel, which is now called Altium, another Australian company, which basically I was doing the printer circuit boards with that. And then at the time, I started doing the CAD work, I discovered, you know, I went through all the different packages, you know, and the one that I ended up using was one called SolidWorks. And the good thing about SolidWorks was that the way you developed something you had like a, like a high, like a hierarchy tree where you did things. And then of course, if you wanted to change that, you go back to the tree to an earlier part a little bit, and then that impacts the rest of it. Yeah, so you were able to do all sorts of crazy things. But the interesting thing for me was because I never studied engineering, I didn’t look at the program like a, engineer looked at it. I looked at it like an artist would look at it. Meaning I was always trying to find things that I could do with a technique that would give me some other result. So in other words, you’re always trying to subvert. It’s like, for example, I did a documentary called, ah, Kiss of Art. And basically I was interviewing all these hybrid digital artists, these modern conceptual artists, as well as real digital artists with interactive art and all this sort of stuff. And in a lot of cases, what these guys were doing was taking like military software and then misappropriating it to make art. there’s a guy from South America who was using facial recognition software to do like, installations and galleries and all this sort of crazy stuff. So for me, I was inspired by the way these guys were dealing with technology. And I was trying to do the same thing with SolidWorks. I was thinking, okay, how can I do my little subverting stuff with SolidWorks? Because then whatever you do can’t be copied because it’s quite unusual and it’s not literal. So anyway, so I started playing with that at the same time in Melbourne there was a guy who used to also offer a package that would work with SolidWorks that could do 3D realizations of the printed circuit boards as well. So, okay, so I was able, 24 years ago to be able to take, a design in 2D, make it 3D, and then of course, add the PCB into it so I could see if it was fitting or not fitting. Because prior to that to do prototyping was ridiculously expensive, you

know, to make a case and then find that after you’ve done all this machining that nothing fit and all this sort of stuff, that basically would kill a lot of projects. So I was able to do all the development work in CAD and then even the, with Protel and the CAD work, the printed circuit boards in CAD as well. So I was able to marry it all together and have a really good look at it, spin it around, get my brain around it, and then say yes or no. So Basically that happened 24 years ago, but it didn’t, the realization, for audio wasn’t There, because I was doing it actually for jewellery, I was doing it for furniture, I was doing it for other companies because I was also. I’ve also been working for people like Esther dupont in Paris for Suiza, which is Le Paire clock company in Switzerland, which is now owned by lvmh. so I was, you know, my parallel careers was also consulting and working in the luxury business. And, through the documentary Lucky.

Andrew Hutchison: Hey. So then, then you had enough income to afford to be in the HiFi businesses as well?

Kostas Metaxas: No, no, no, no. It wasn’t like that at all, to be honest, because, like, everything, everything makes. Makes whatever it makes. But, the truth of the matter is what that afforded me was an understanding of the luxury business. But I have to add a caveat, which was that the luxury business I loved and grew up with in the 80s had vanished by the mid-90s, because now all these companies became basically Procter and Gamble and Unilever doing, you know, expensive handbags. you know, you can’t. For example, Louis Vuitton has six factories in Paris and their production is the equivalent of 60 factories. So clearly it’s not. Everything’s done in Paris. So basically what I’ve learned was that all these companies now had gone off and all their executives were just, you know, basically used to sell cornflakes and Vegemite. So, and butter. Now they’re selling, you know, you know, perfumes and all this sort of stuff. So. But luckily in the 80s, when I first started, mid-80s, I was. When I was doing a magazine at the time, I was able to visit Paris and talk to. When I was talking to jewelers, I was talking to the actual families. The guys that started the companies before they were all bought out by these big conglomerates. So when I went to see Christophe, the cutlery company, it was Henri Boullier, his brother Elbe Boullier. When I went to see Boucheron, the jeweler, ah, it was Alain Boucheron. When I went to see Hermes, which has become a huge business, it was Jean Louis Dumas, who was the genius of the luxury business. So I got to meet the guys that were really the movers and shakers and then at the same time, the architecture with jewelry, with fashion. You know, I interviewed people like Uber de Givenchy or Pierre Cardin. I remember sitting with Pierre Cardin in Paris at that time. He was like, past the fashion site, he was doing furniture and stuff. And, you know, it was. You’re sort of starting to understand another level of thinking of how to understand aesthetics and art history. And that’s where the new stuff comes from. So that’s why it’s so off the planet compared to what. But basically what I tried to then do, and this was, this was really with the collection from 2015. So it’s about 10 years ago. 10 years ago I was doing furniture and all this stuff and I thought, okay, maybe now I can look at HiFi with the same eyes and. Because otherwise if I had to do another box, I wouldn’t bother. It’s just no point. There’s just too much of that. Right.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah. well, this. Yeah, I mean, so that’s interesting because timeline wise, I feel that’s when I first saw your. Maybe when was the first time you went back to Munich with the new stuff? Was that 2015, 16 or something?

Kostas Metaxas: Something, yeah, exactly, 2016.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah. And I’m like, this is. Yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: But I had a guy, I had a guy who was in France and they were a distributor of some speakers and stuff. They wanted to distribute my stuff, but they had in mind the stuff I was doing like, you know, 20 years earlier.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah, yeah.

Kostas Metaxas: And, I said to them, guys, what I’m doing now is totally different to that. You know, they said, oh, okay, no problem. Let’s do a show in, in, Munich. So they said, let’s. Okay. I said, that’s no problem. So they told me when they needed me to be there, what to deliver, blah, blah, blah. And that’s when I delivered the new stuff. Which totally, you know, I think was a big shockwave to the whole audio world because, well, firstly they saw this crazy shit, but they thought, I can’t. He’ll do one, one hit wonder, he’ll do this crazy shit and that’ll be the end of it. And of course, they didn’t know, you know, what I’d already been doing and who I’ve been talking to and, and all this sort of stuff. So that’s of course why they don’t realize why I’m doing all this crazy shit.

When you analyze other luxury businesses, high end audio hasn’t evolved very much

And the reason is very simple. When you analyze, when you look at the rest of the luxury businesses, the one that hasn’t been, you know, quite frankly, hasn’t evolved very much is high end audio of all of them. Cars have gone to, you know, incredible dimensions. Watches, fashion, all that stuff. And high end audio really, you know, a lot of people haven’t sort of, you know, seen the light there. And of course the irony was at the time I was actually thinking of Doing watches or something else. But then I thought to myself, God, with watches and that there’s thousands of great companies that are doing stuff that, you know, I find it difficult to compete with.

Andrew Hutchison: Yes.

Kostas Metaxas: And the irony was in high end audio, it was a basically, you know, virgin territory. No one had bothered to do museum quality, high end audio aesthetically that are going to be objects of art in the future. And that’s the only way you’re going to survive. Because you and I know when an amplifier is second best and third best and fourth best, it’s worthless. And the only way to give it some worth, some value is intrinsically with its sculpture. And that’s the thing that I try to do. And that’s why ironically, people who don’t get it now, it’s not a problem because there’s enough of a market that I can survive and do what I want to do. But in the future, if you go 20 or 30 or 50 years from now, you will see my objects coming up in Sotheby’s or Christie’s. Because it’s like for example, what Mark Newson was doing. Mark Newson, as you know, another Australian, also another Greek by the way. he, he basically did to furniture, you know, what I’m doing to high end audio. So basically what he did was he created some lounge chairs at the time and the one one was sold for $20 million at Christie’s, a few years back. So, you know, he sold it for $20,000 back. Yeah, $20 million exactly.

Andrew Hutchison: So I’m going to admit my, there’s a gap in my knowledge there and I like, I like esoteric, interesting furniture. But I guess when I see the piece, when I look it up, when I get off the line with you, that I’ll go, ah, yeah, that’s it. But that’s, that’s that’s astounding. and of course you’ve, you’ve, you’ve hit a, I mean, man, we used to make some fantastic furniture in this country. Wow. I mean we really did. There’s not, there’s not much made here now. Not really, no. I mean there’s not much of anything made here now compared with, with perhaps, well, when it comes to furniture, 70s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s and, and, and to some degree in the 90s. But then someone turned a switch off in the year 2000 and that was that. and it’s been going downhill since. But yeah, now I’m going to look that up. Look. I agree, that the, the audio industry kind of stuck with boxes and varying degrees of very high quality boxes. But I suppose Mr. M. D’ Agostino has probably got some of the more interesting looking stuff out there at the moment. And and then there’s the Is it a Korean company? Perhaps Rose have that integrated amp with all the cogs and dials and wheels on the front which is kind of cool. But other than that I can’t think of anything other than yours which has got any kind of, I mean Nagra. Yeah. Have used their styling language to create some very pretty amplifiers that are no doubt beautiful, beautifully made and have great knob feel. but there’s, there’s, there’s not a lot of it out there, is there? And so yours stands out. but I guess at the same time, knowing the cons, the conservative nature of the audio customer, seemingly that there are people who would perhaps rather like the sound of your gear and can afford it but wouldn’t buy it because of the way it looks. And I guess those people come up to you at the show and tell you all about it. Is that, is that right or not? When I say the show? You go to many shows, I guess, but Munich is where where I’ve you know, seen your product more recently.

Kostas Metaxas: Yeah. Basically I think, obviously the customers that I used to have in the 90s, you know, they’re still there and I still, I still have them as customers too, believe it or not.

Andrew Hutchison: Yeah.